A comparison of dog and wolf DNA reveals interesting genetics behind domestication. The new study is a step toward a deeper understanding of evolution for dogs and humans alike.

8:00 PM

Author |

From pugs to labradoodles to huskies, dogs are our faithful companions. They live with us, play with us and even sleep with us.

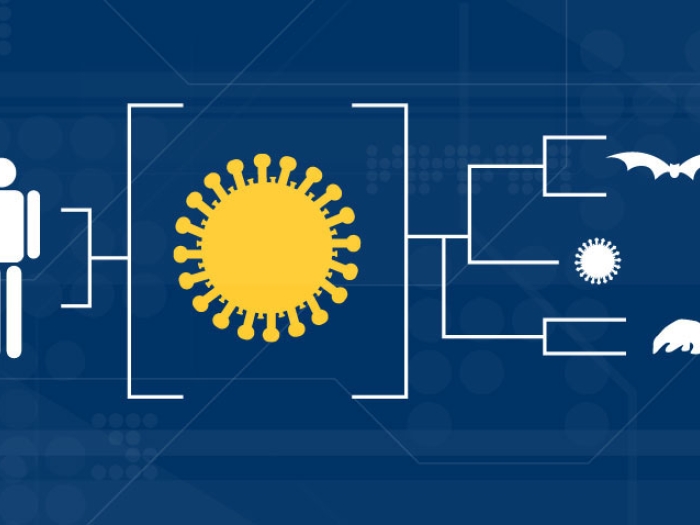

But how did a once nocturnal, fearsome wolflike animal evolve over tens of thousands of years to become beloved members of our family? And what can dogs tell us about human health?

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Through the power of genomics, scientists have been comparing dog and wolf DNA to try and identify the genes involved in domestication.

Amanda Pendleton, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow in the Michigan Medicine Department of Human Genetics, has been reviewing current domestication research and noticed something peculiar about the DNA of modern dogs: at some places it didn't appear to match DNA from ancient dogs. Pendleton and her colleagues in assistant professor Jeffrey Kidd, Ph.D.'s laboratory are working to understand the dog genome to answer questions in genome biology, evolution and disease. Their latest work is published in BMC Biology.

"We convinced ourselves that previous studies found many genes not associated with being a dog but with being a breed dog," says Pendleton.

Breed dogs, which mostly arose around 300 years ago, are not fully reflective of the genetic diversity in dogs around the world, she explains.

Three-quarters of the world's dogs are so-called village dogs, who roam, scavenge for food near human populations and are able to mate freely. In order to get a fuller picture of the genetic changes at play in dog evolution, the team looked at 43 village dogs from places such as India, Portugal and Vietnam.

Armed with DNA from village dogs, ancient dogs found at burial sites from around 5,000 years ago, and wolves, they used statistical methods to tease out genetic changes that resulted from humans' first efforts at domestication from those associated with the development of specific breeds. This new genetic review revealed 246 candidate domestication sites, most of them identified for the first time by their lab.

Now that they'd identified the candidate genes the question remained: What do those genes do?

[F]loppy ears, changes to the jaw, coloration, tame behavior can be explained by genetic changes ...Amanda Pendleton, Ph.D.

'A good entry point'

Upon closer inspection, the researchers noticed that these genes influenced brain function, development and behavior. Moreover, the genes they found appeared to support what is known as the neural crest hypothesis of domestication.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"The neural crest hypothesis posits that the phenotypes we see in domesticated animals over and over again — floppy ears, changes to the jaw, coloration, tame behavior — can be explained by genetic changes that act in a certain type of cell during development called neural crest cells, which are incredibly important and contribute to all kinds of adult tissues," explains Pendleton.

Many of the genetic sites they identified contained genes that are active in the development and migration of neural crest cells.

One gene in particular stuck out, called RAI1, which was the study's highest ranked gene. In a different lab within the Department of Human Genetics, Michigan Medicine assistant professor Shigeki Iwase, Ph.D., has been studying this gene's function and role in neurodevelopmental disorders. He notes that in humans, changes to the RAI1 gene result in one of two syndromes — Smith-Magenis syndrome if RAI1 is missing or Potocki-Lupski syndrome if RAI1 is duplicated.

"RAI1 is a good entry point into studying brain function because its mutation results in a brain disorder," he says. "Studies suggest that this protein controls the expression of several genes involved in circadian rhythms. One of the unique features in these conditions is the problem these patients have with sleep."

In dogs, changes to this gene may help explain why domesticated dogs are awake during the day rather than nocturnal like most wolves. Other genes Kidd's lab identified in dogs have overlap with human syndromes resulting from improper development of neural crest cells, including facial deformities and hypersociability. These parallels between dogs and humans are what make understanding dog genetics valuable.

Kidd explains, "We are using these changes that were selected by humans for thousands of years as a way to understand the natural function and gene regulatory environment of the neural crest in all vertebrates."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!