When high-risk patients need surgery, doctors might take a cue from coaches. A U-M program is helping some clinicians draft the playbook.

7:00 AM

Author |

A seasoned athlete wouldn't compete in the big game or attempt a long-distance race without training for optimal performance.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

And patients prepping for surgery shouldn't either — meaning doctors ought to emphasize the value of conditioning long before a person enters the hospital.

"In both cases, there's a kind of shared physiology behind the training," says Michael Englesbe, M.D., a transplant surgeon at the University of Michigan Health System. "Functional disability underlies a lot of bad outcomes."

General wellness objectives, then, are crucial: a healthful diet, proper exercise, alcohol and tobacco cessation and stress reduction, among other things.

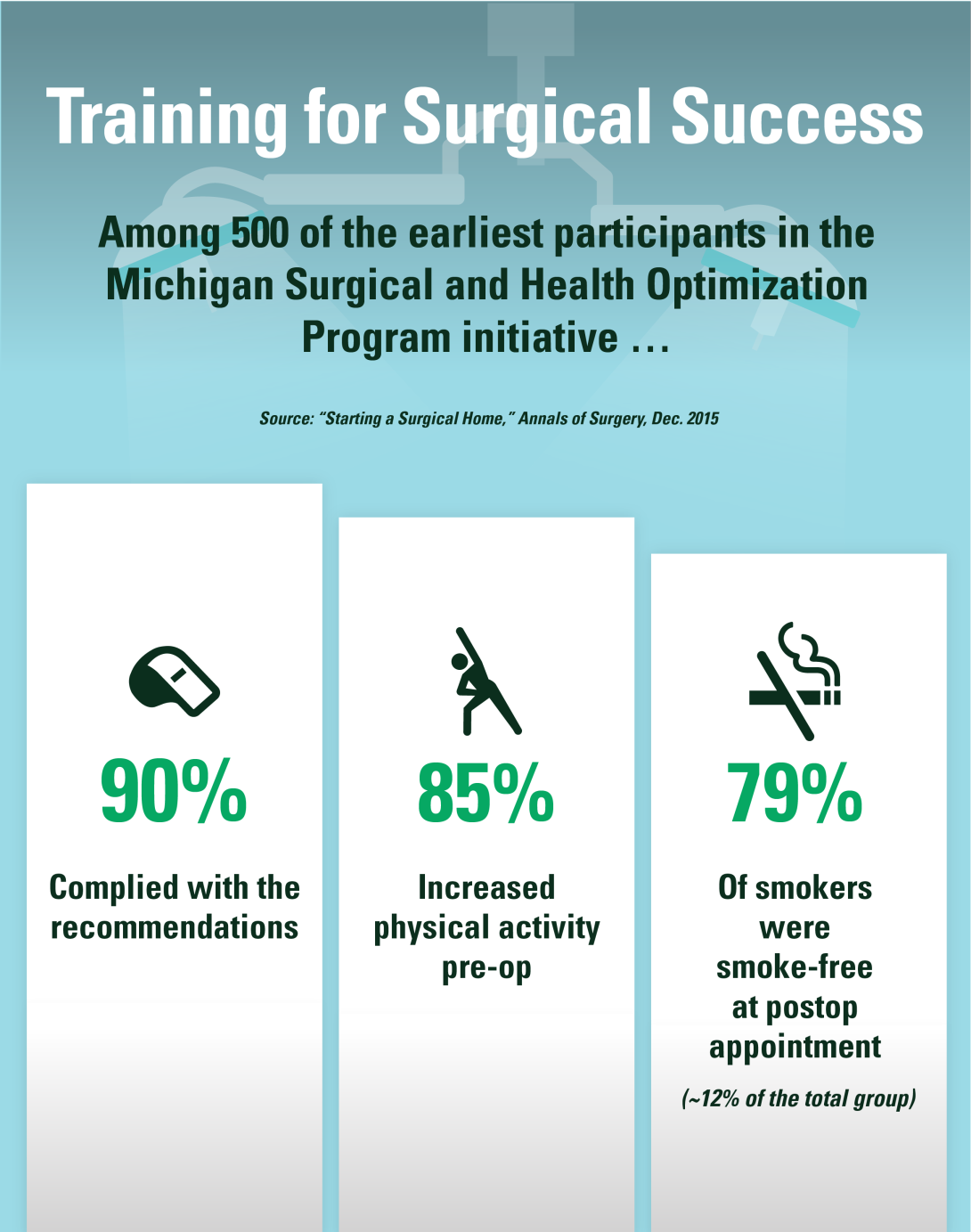

Which is why Englesbe helped conceive the Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP), an initiative aimed at helping patients target and strengthen their weaknesses before surgery — efforts that, based on risk and adherence, could delay admission dates in nonurgent cases.

The outcomes that can result are worth the extra wait and work, Englesbe says, including shorter recovery time, reduced likelihood of readmission and lower medical costs.

A proactive approach might also offer added comfort and confidence during a time of high anxiety.

"Patients often feel very powerless when they're having big operations," Englesbe says. "Anything we can do to empower them to have some control of their outcome in what is inherently a situation they can't control very well is a good thing."

Partners in training

Englesbe, along with UMHS trauma surgeon Stewart Wang, M.D., Ph.D., FACS, began developing the MSHOP concept in 2010.

The pair rooted their research in the study of morphomics, or the analysis of patient data used to deliver personalized health care with optimal results.

"We did a lot of work trying to predict who would do poorly after surgery," Englesbe says, noting that preventable frailty because of poor diet or inactivity before a procedure was found to be a key predictor of post-operative complication. "It became obvious a lot of patients struggle with [prior] functional issues. We came up with the idea that people should start training to combat that … to augment the recovery."

The pilot MSHOP program, launched one year later in partnership with the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, adopted a multipronged approach.

Using a web-based risk assessment tool, doctors can input a patient's age, weight, existing health issues and intended surgery, as well as other factors, to devise specific nutrition, exercise and emotional goals.

To help patients get moving, for example, daily text messages are sent reminding a person to meet (or exceed) a predetermined amount of steps tracked with a pedometer.

Collectively, "You're tapping them on the shoulder," Englesbe says. "It doesn't mean 'We're watching you.' Instead, it's saying 'We're with you.'"

Keeping score

A small review of early MSHOP participants showed promise. Compared to a control group, those who followed a preparatory routine went home 2.3 days sooner and saved an average of $2,308 in hospital costs.

The financial advantages, Englesbe says, can't be overlooked: "Patients who are frail cost payers and hospitals a lot of money."

Taking simple measures to, say, control diabetes (which can otherwise affect a wound's healing ability) or lose weight to reduce the risk of infection after knee surgery can add up in the long run.

The MSHOP project, which won a $6.4 million Health Care Innovation Award by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2013, has continued to grow. The voluntary program has now expanded to 22 medical practices and hospitals across Michigan.

With about 25 new patients enrolling in MSHOP per week, the movement affects just a sliver of the 65,000 operations performed annually at UMHS.

Clinicians, then, must be the ones to initiate the conversation and help inspire action.

"I think it starts with the surgeon at the time of decision (to proceed with surgery)," says Englesbe. "Everyone should train for surgery. It's a cultural change."

Everyone should train for surgery. It's a cultural change.Michael Englesbe, M.D.

A "transformed" attitude

Much like one builds up endurance before a marathon, results can't happen overnight.

SEE ALSO: To Reduce Hysterectomy-Related Readmissions, Target Those at Risk

Because 90 percent of surgeries in the United States are elective, doctors have ample time to explain the "training" particulars and allot patients a sufficient window (about 30 days will do, Englesbe says) to adopt and sustain the necessary lifestyle changes.

Lessening internal worries in the process, Englesbe adds, may give the patient a sense of peace when the big day arrives — a notion of "I did everything I could."

Perhaps more vital, the MSHOP curriculum can lay the groundwork for positive habits that continue long after hospitalization ends.

Englesbe recalls the recent case of a man on whom he performed a splenectomy. The patient, though only in his 20s, had a host of severe comorbidities and was at first reluctant to act on the MSHOP recommendations in advance of surgery.

Then, he did.

"He went from walking 1,000 steps a day to 10,000 steps a day over 3 1/2 weeks," says Englesbe. "I said to him: 'Oh, my gosh, this is really remarkable how much you prepared for this.'"

Before the behavior change, the intensive surgery could have netted serious complications. But thanks to his training, the patient's outcomes improved.

Says Englesbe: "It really changed the way we went into the operation — and it transformed his course."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!