A deep dive into logbooks from the father of a surgeon reveals what surgery on the battlefields of World War II was really like.

10:26 AM

Author |

Like any good trauma surgeon, Richard Burney, M.D., has done his share of putting injured bodies back together.

Retelling the story of a World War II surgeon's experience on the front lines, through a paper recently published in the Journal of Trauma, required a different kind of reconstruction: joining together personal narrative and recorded history.

Burney's endeavor started with a Grand Rounds talk by Darrell (Skip) Campbell Jr., M.D., former chief medical officer at University of Michigan Health and professor emeritus of transplant surgery at Michigan Medicine, around the anniversary of D-Day last year.

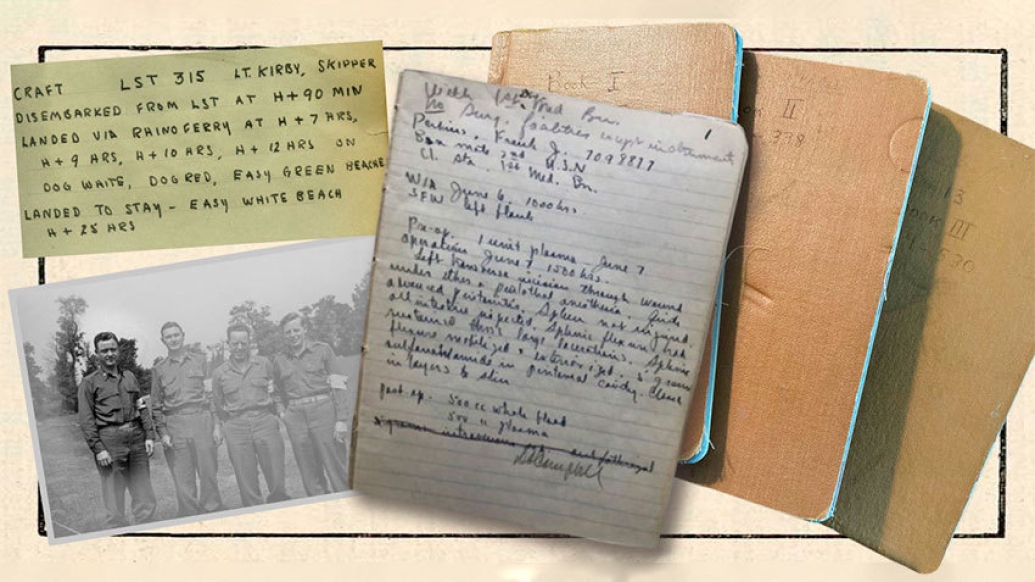

His father, Darrell Campbell, M.D., served in the United States Army during World War II as a surgeon and kept logbooks of the battlefield operations he and two other surgeons performed. He had completed a three-year surgical residency at University of Michigan Hospital in 1939 and stayed on as a cancer researcher and instructor for two years before entering the U.S. Army Medical Corps and deploying to Europe shortly after the start of the war.

The talk gave attendees — which included Burney, a professor emeritus of surgery at Michigan Medicine — a taste of those books. But Burney wanted to know more about the experience of being a surgeon on the front lines.

"I stopped by Skip's office after the presentation and asked him if I could see the logbooks," Burney said. "They constituted a primary historical record that should have been turned into the Army at the end of the war, but for whatever reason, wasn't."

Campbell was happy that someone else was interested in digging deeper, knowing that analyzing personal history can be more difficult when you're close to the subject. Burney understood that feeling; he'd recently begun to look at a memoir his own father had written but never discussed.

SEE ALSO: Health on the Homefront: Efforts to Improve Civilian Care for Veteran

"The serendipity was interesting because around the same time I had run across a memoir my dad had written about growing up in Ireland during the Irish rebellion or 'Tan War' from 1916 to 1921," Burney said. "We had both discovered these things that our parents didn't talk about."

Following a passion to tell a story

Burney wasn't sure where the journey would lead when he started reading the logs. He hoped to understand better what battlefield surgery was like and, if possible, delve into the emotions these WWII surgeons were feeling as they worked. To do this, he needed to immerse himself in their experiences while also putting their records into historical context.

For Campbell, the essential context was the chaos of the Omaha beachhead on D-Day, which he'd written about in an essay published last year in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

"That was why I wrote that paper in the first place, to bring up the idea that this was really remarkable," Campbell said. "We think we have it bad with the pandemic. That generation had it bad with a world war."

A lucky break was finding that Maj. Campbell's surgical team was part of the Third Surgical Auxiliary Group, initially organized in May 1942. One of the first people assigned to it was Army Capt. Clifford Graves. After the war, Graves had written a book, Front Line Surgeons: A History of the Third Auxiliary Group, describing its history and recording its activities, including many firsthand accounts. That book provided much of the needed military background.

Maj. Campbell's subgroup, the Third Auxiliary Surgical Team 13, included two other surgeons, an anesthesiologist and four enlisted personnel acting as technicians. If two members of the team worked together, the lead surgeon on the case wrote the operative note.

The logbooks contained hand-written operative notes, one per page. Most were in ink and remarkably well preserved. Burney was struck by the legibility of the handwriting and the economy of the operative notes. Individually, they were dispassionate in their descriptions, but, collectively, they illustrated a struggle to deal with the stream of casualties. From other historical sources, he was able to correlate them with the geography and timeline of the war in Europe: where the troops were, what hospitals they were assigned to and when they moved from one hospital to another.

Burney saw the logbooks as an untapped data source. He thought it would be helpful to convert the notes into data, a task with which he had plenty of experience: While serving as chair of the Michigan Committee on Trauma and a member of the Committees on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons, Burney helped develop the trauma data collection system that became the National Trauma Registry of the ACS.

SEE ALSO: How Academic Medical Centers Came to Be

Burney transcribed the notes into a new document to avoid repetitive page flipping that could damage the logbooks. He coded injuries and operations by type in a spreadsheet for analysis, a process the young Maj. Campbell surely never anticipated while dashing off notes from a muddy tent.

"I gathered all the facts about injuries, operations, locations and types of mobile hospitals," Burney said. "I was particularly interested in what operations were actually being done. For most of my generation, the only image we have is what we saw in M*A*S*H. I was curious to know what the causes of most of the injuries seen during World War II were and how they were treated."

A passage to another time

The logs covered the period from June 7 to December 13, 1944, revealing patterns and trends in the details about the team's surgeries and the injuries they treated: how injuries changed relative to proximity to fighting, when the location of the hospitals changed, how different circumstances affected surgery delays and how approaches evolved based on these factors.

The first logbook began on June 7 with an entry from Omaha Beach shortly after a dangerous and chaotic landing. The last logbook ended with an entry from a site in Germany on December 13, mere days before the Battle of the Bulge.

It was a story our fathers didn't want to talk about but that had to be told, a search for truth.Richard E. Burney, M.D.

The first entry describes the desperate conditions and lack of supplies, some of which had gone overboard or been delayed by the chaotic beach landing:

With 1st Div. Med(ical) B(attali)an. No surg(ical) facilities except instruments.

The facilities the group worked in included collecting and clearing stations, evacuation hospitals and field hospitals. Collecting and clearing stations, closest to the front, were mainly triage centers. Soldiers with lesser injuries and extremity wounds were sent to evacuation hospitals, also close to the front. Those with chest and abdominal injuries were supposed to be sent to field hospitals, which provided more specialized care, but in practice the roles of evacuation and field hospitals sometimes overlapped.

"Everybody's image of battlefront surgery is of Donald Sutherland in the movie M*A*S*H, and later Alan Alda in the television series," Burney said. "In some ways, that's pretty accurate."

What fiction and fact had in common was the primitive setting: canvas tents, dirt floors, basic forms of anesthesia and a lack of modern equipment. The surgical teams often needed to get creative. Innovations ran the gamut from hanging canvas sheets to prevent dirt from entering the tents and compromising the operative field to inventing procedures on the spot.

"Dad saw a lot of sucking chest wounds with fractured ribs and gaping openings into the chest that had to be closed somehow," Campbell said. "He devised an operation, a vascularized flap, where he would detach the latissimus dorsi muscle [what's commonly known as the lat muscle in the back], swing it as a flap over the hole and then close the skin over that." (The elder Campbell wrote about the procedure after the war in the Journal of Surgery, and the technique is now widely used.)

As the Army pushed on from France into Belgium and finally Germany, the injuries trended toward those from shell fragments instead of gunshot wounds, as mortar fire from the Germans became the more common weapon of choice.

"I thought I would read about people getting shot, but instead, they were injured by shell fragments," Burney said. "When a shell hits the ground, it explodes and sends high-speed fragments everywhere."

Details reveal trauma to patients and surgeons

Aside from the trends the notes revealed, Burney was struck by their insight into the surgeons' thinking—which he thinks current electronic medical records lack because of their templated style.

"If you pull up an operative note today, you'll find it much more sterile," Burney said. "There's something very important about putting experiences into words. It's important to sit down and reflect on what's going on or why you did what you did. Narrative does that; it helps turn information into understanding."

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcast or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

For example, the following note puts the implied decision-making process on display, reveals the stress the team was under and expresses the surgeons' concerns about the patient described.

#91 J.C. Co A

WIA Artillery shell 1300 hrs 30 June

Pre-op 3000 cc blood 750 cc plasma

Op 1400 hrs 1 July Pent. & ether

After being in shocked state for 24 hrs, not permitting surgery it was felt he was now at his optimum for necessary surgery. Pt had tremendous extensive soft tissue injuries to both lower extremities, especially right thigh and buttock c fractured pelvis, damaged rectum, extraperitoneally, & fractured os calcis, left. Wounds excised, sulfa & packed with Vaseline gauze. Bilat hip spica applied. Left ant area of abdom part of spica cut away and simple sigmoid colostomy done thru McBurney type incision.

1500 cc blood given during & immediately after op. Cond. still poor, probably in irreversible shock.

1st p.o. day Cond. good.

DACampbell/JPSheldon

Postscript: Died on 7-8 po day obstruction ? colostomy

An unsigned entry from among the first days in the field, about leaving the clearing station on the beach to work in an EVAC hospital, was short on detail but long on emotion:

Leaving 1st Div. Med. Bn. Thank God!

Whenever possible, Maj. Campbell followed up with post-operative notes, sometimes recording seemingly miraculous recovery but more often jotting down complications and deaths that revealed the stark reality the team was dealing with: a roughly 15% post-op mortality rate.

"You knew it was hard if 10-15% of the people you operated on died—and you only operated on the people you thought you could save," Burney said. "That's got to take a toll emotionally."

It did take a toll on Maj. Campbell.

After returning home, he was a surgeon in private practice for 35 years at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor. In his later years, he experienced depression and alcohol and drug dependence, according to the younger Campbell's essay.

Deciding to share those details wasn't an easy decision. After consulting with his siblings, Campbell decided that not sharing them would be a disservice to others experiencing trauma, including today's surgeons.

"We minimize the trauma soldiers and others have from their jobs," Campbell said. "There's this barrier between the generation that was in the war and the more recent generation. They just didn't want to talk about it. They had some serious mental trauma and in my dad's case, he buried it deep in his brain."

The connection between the surgeons

Once Burney had operative data on a large spreadsheet and had gathered as much historical material as he could, he started on the story that had been waiting to be told: not the usual academic surgical paper but rather a hybrid, a narrative woven from established history and the logbooks. He shared it with Campbell, who thought it deserved a home due to its scholarly approach.

Burney contacted the author of a commentary on Campbell's essay, Margaret "Peggy" Knudson, M.D. (also a U-M trainee), and the wheels were soon in motion for his piece to find a home in a military supplement to the Journal of Trauma.

The project was an interesting footnote in a long career that began shortly after Burney himself served in the U.S. Army, right after the Vietnam War had ended.

"I was mentally preparing to get shipped off to Vietnam, but fortunately that conflict ended a few months before I finished residency," Burney said. "I spent two years at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, taking care of unhappy officers who returned from Vietnam and weren't sure what they were going to do because there was no war to fight."

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

When he finished his military commitment, he heard the U-M Department of Surgery was looking for someone to run a nascent emergency department. Since Burney had done research on emergency department function and taught pre-hospital care in the Army, he was offered a job.

As a trauma surgeon, he helped establish the pre-hospital care system in Washtenaw County, now Huron Valley Ambulance Service, and was later the medical director of Survival Flight.

It's a long way from the modern OR to the muddy battlefields of 1944 France and Germany, but the themes Burney uncovered in logbooks of the past can teach us something about the present, he says.

"We're becoming increasingly interested now in using social science to examine the practice of surgery," Burney said. "More is being published about how you feel about things like stress and burnout. This project was an opportunity to delve into history using a unique primary source. It was a story our fathers didn't want to talk about but that had to be told, a search for truth."

Paper cited: "D-Day to December 1944: The Odyssey of the Third Auxiliary Surgical Group in World War II," The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003205

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!