Study shows early treatment with specific antibiotics depletes the body of gut anaerobes that protect against pneumonia, organ failure and mortality.

5:00 AM

Author |

A common clinical practice may be inadvertently harming patients, according to research published in the European Respiratory Journal. The team of Michigan Medicine researchers behind the study suggest that administration of antibiotics with activity against anaerobic bacteria has a profound effect on the gut microbiome and, ultimately, an adverse impact on critically ill patients.

"We talk about the gut microbiome as a metabolic and immune 'organ,' and when we give patients anti-anerobic antibiotics, I worry we are causing a hidden form of organ failure," said senior author Robert Dickson, M.D., associate professor in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and Deputy Director at the Weil Institute for Critical Care Research and Innovation at the University of Michigan. "Our research suggests that depleting the gut of these 'good bugs' may be contributing to worse clinical outcomes."

In the paper, researchers found that, in critically ill patients, the practice of early administration of anti-anaerobic antibiotics is commonplace – about two-thirds of the 3,032 patients observed in the study's cohort received such treatment.

"For sick patients in the Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit, there has been a lot of focus on 'time-to-antibiotics' as a quality improvement measure," said Dickson. "Our results demonstrate that antibiotics really can't be considered a single entity, as they have widely different impacts on the microbiome and on our patients. Patients who received anti-anaerobic antibiotics did far worse than patients who didn't. We think that which antibiotic is given probably matters more than how quickly they are administered."

With support from the Weil Institute, along with funding from the National Institutes of Health, the researchers conducted a retrospective single-center cohort study of 3,032 critically ill patients, comparing those who did and did not receive early anti-anaerobic antibiotics. By comparing ICU outcomes in all patients, and changes in gut microbiota in 116 of the patients, they found that those who received anti-anaerobic antibiotics early in their hospital course had worse outcomes, whether measured in overall survival, infection-free survival, or pneumonia-free survival.

The authors also found dramatic consequences of these antibiotics on the gut microbiome – during hospitalization, patients who received anti-anaerobic antibiotics had decreased initial gut bacterial density, followed by increased expansion and domination of the microbiome Enterobacteriaceae (a genus of common bacteria, many of which are pathogenic and cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised hosts.) These findings confirm that anti-anaerobic antibiotics have a dramatic effect on gut bacterial communities.

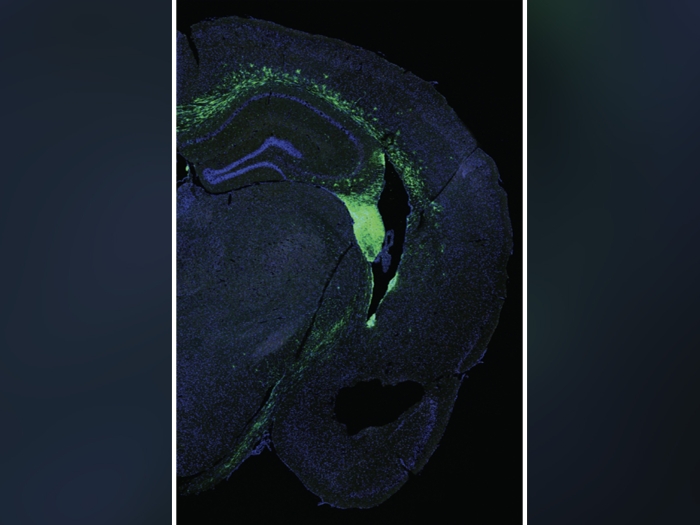

While the primary findings were from an observational study in humans, the team confirmed the results using animal modeling. In two different mouse models (pneumonia and oxygen-induced lung injury), animals who were treated with anti-anaerobic antibiotics did worse. Anti-anaerobic antibiotics increased the susceptibility of mice to pneumonia due to Enterobacteriaceae and increased their mortality from oxygen toxicity.

Co-author Rishi Chanderraj, M.D., a clinical lecturer in Infectious Diseases at U-M, was the lead researcher on the initial project and will be carrying the work forward in future studies.

"In observational studies, there is always a risk that a mortality difference is due to confounding; maybe the patients who received anti-anaerobic antibiotics were just sicker," he said. "But the fact that we were able to recapitulate these findings in two different animal models gives us confidence that these findings are real."

"No one wants to withhold antibiotics from patients with life-threatening infections," said Chanderraj. "But our study confirms that the risk of overtreating with antibiotics isn't just theoretical. I'm concerned that we're harming our patients."

Paper cited: "In critically ill patients, anti-anaerobic antibiotics increase risk of adverse clinical outcomes," European Respiratory Journal. Need citation link

About the Weil Institute, formerly MCIRCC

The team at the Max Harry Weil Institute for Critical Care Research and Innovation (formerly the Michigan Center for Integrative Research in Critical Care) is dedicated to pushing the leading edge of research to develop new technologies and novel therapies for the most critically ill and injured patients. Through a unique formula of innovation, integration and entrepreneurship that was first imagined by Weil, their multi-disciplinary teams of health providers, basic scientists, engineers, data scientists, commercialization coaches, donors and industry partners are taking a boundless approach to re-imagining every aspect of critical care medicine. For more information, visit weilinstitute.med.umich.edu.

Live your healthiest life: Get tips from top experts weekly. Subscribe to the Michigan Health blog newsletter

Headlines from the frontlines: The power of scientific discovery harnessed and delivered to your inbox every week. Subscribe to the Michigan Health Lab blog newsletter

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!