Genetics experts used to think the Xist gene acted alone in silencing X chromosomes. But researchers say it has accomplices — and the implications matter for treating X-linked diseases.

4:24 PM

Author |

Nearly every girl and woman on Earth carries two X chromosomes in nearly every one of her cells — but one of them does (mostly) nothing. That's because it's been silenced, keeping most of its DNA locked up and unread like a book in a cage.

Scientists thought they had figured out how cells do this, but a new piece of research from the University of Michigan Medical School shows the answer isn't quite so clear.

Their findings could help lead to new ways of fighting diseases linked to X chromosomes in girls and women — the kind that occur when the X chromosome that does get read has misprints and defects. These include a wide range of relatively rare diseases, as well as relatively common conditions such as autism, hemophilia and muscular dystrophy.

In a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U-M genetic researchers show that a molecule called Xist RNA is insufficient to silence the X chromosome. The gene for that molecule, Xist, has been seen as the key factor in silencing one of the two X chromosomes in every female cell.

The findings come from the same team that recently showed how a fragment of genetic material made from reading Xist backward, called an antisense RNA, leads to the production of Xist RNA.

"Xist is widely believed to be both necessary and sufficient for X silencing," says team leader Sundeep Kalantry, Ph.D, assistant professor in the Department of Human Genetics. "We for first time show that it's not sufficient, that there have to be other factors, on the X-chromosome itself, that activate Xist and then cooperate with Xist RNA to silence the X-chromosome."

What's more, Kalantry says, in the future it may be possible to change the level of these other factors in cells and turn on the healthy, silenced copy of a gene that lies on the inactive X-chromosome.

In females, we could envision 'reawakening' a healthy copy of an X-linked gene on the inactive X chromosome, by modulating the dose of these so-called escapee genes and ameliorating the effects of the unhealthy copy.Sundeep Kalantry, Ph.D.

What is Xist?

The Xist gene, short for X-inactive specific transcript, is found on each X chromosome. It doesn't tell cells to produce a protein, like most genes do. Instead, it produces Xist RNA that physically coats the entire X-chromosome, and thereby is thought to seal most of it off from the rest of the cellular world.

Now, the U-M group has shown that Xist isn't a lone operator. It has to have accomplices.

They are close to identifying these accomplices. At present, they do know that they reside in a very interesting place: the X chromosome that's destined to get silenced. Although most genes on the inactive X chromosome are fully silenced, a handful of the genes on the inactive X are, in fact, active.

The research team — focused on this set of X-inactivation 'escapees'. Since the 'escapee' genes are expressed from both the active and the inactive X-chromosomes in females, they produce more gene product in female cells than in male cells, which only have a single X.

The study predicts that this higher "dose" in females triggers X-inactivation selectively in females; the lower dose in males is insufficient.

If researchers can determine exactly which factors cause X-inactivation to occur, they could find ways to affect the activity of genes on the X chromosomes —specifically, genes involved in certain diseases.

X marks the spot

Many of the X-linked diseases affect an individual's thinking and memory capacity, and other aspects of cognition and intelligence.

"In females, we could envision 'reawakening' a healthy copy of an X-linked gene on the inactive X chromosome, by modulating the dose of these so-called escapee genes and ameliorating the effects of the unhealthy copy," says Kalantry.

Unfortunately, this approach probably won't help males with X-linked diseases, because they only have a single X chromosome in each cell. Inactivating it would beharmful.

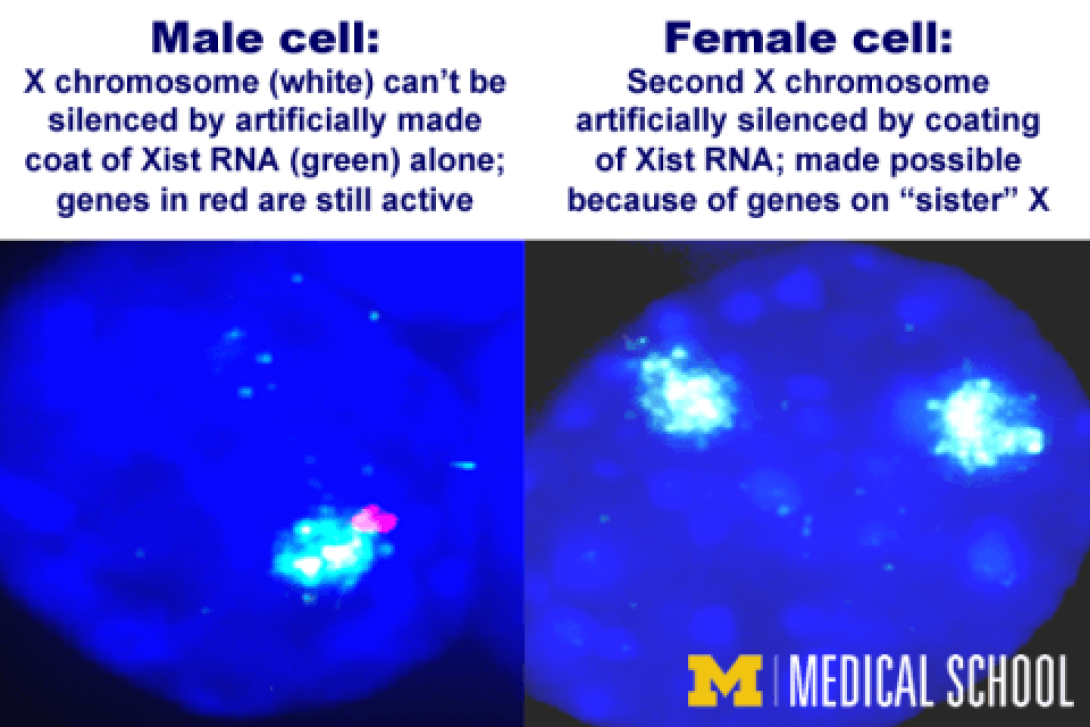

But that's exactly what made the new research possible: The team attempted to silence the sole X chromosome in male stem cells from mice by turning Xist on artificially. As it turns out, they could only silence the X-chromosome genes somewhat — because the male cells had no "twin sister" X chromosome to contribute the genes needed to finish the silencing job.

When the researchers used female cells that had one X that was already inactivated— and therefore had the same number of active X-chromosome as in males — they were still able to silence the active X when they artificially turned Xist on from that chromosome.

The difference was that the female cells had higher levels of products made by"escapee" genes.

Now, Kalantry says, the team is zeroing in on the specific X-inactivation escapee genes that first allow for Xist RNA to be expressed and then work with Xist to make silencing possible.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!