Halting the voyage of gut bacteria to the brain could help prevent harmful brain inflammation after a sepsis infection, a new study shows.

7:00 AM

Author |

Surviving a critical illness is no small feat, but it's only half the battle for many patients. Serious complications can still result after an illness appears to have cleared.

One of those resulting dangers is brain dysfunction.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"Many will experience cognitive impairments or emotional difficulties that are equivalent to mild traumatic brain injury and can persist for months or years after their hospitalization," says Benjamin Singer, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of internal medicine at Michigan Medicine.

The source of that impairment isn't always clear, however.

Singer is the lead author of a study, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, that sought to examine a potentially serious connection: whether gut bacteria cause brain dysfunction in sepsis patients.

"We already know from previous studies that sepsis results in long-term brain dysfunction and that neuroinflammation plays a role in brain injury during the infection," says Singer, who specializes in pulmonary disease and critical care medicine.

"But we hypothesized that the brain injury is directly related to gut bacteria independently moving to the brain and perhaps triggering an immune response that leads to longer-term effects from the injury."

Common thread in mice and humans

Although previous studies have suggested that gut microbes, or microbiome, may increase the likelihood of lung inflammation during sepsis, Singer and his research colleagues note that the microbiome's effect on other organs, such as the brain, has been unstudied.

SEE ALSO: Gut Bacteria Leads to Obesity? Not So Fast

Singer and the team used mice models and brain tissue of deceased patients (the latter source came from the University of Michigan Brain Bank) to carry out the study. Mice that survived sepsis were compared with mice controls; brain tissue of patients who died of sepsis was compared with tissue of patients who died of noninfectious causes.

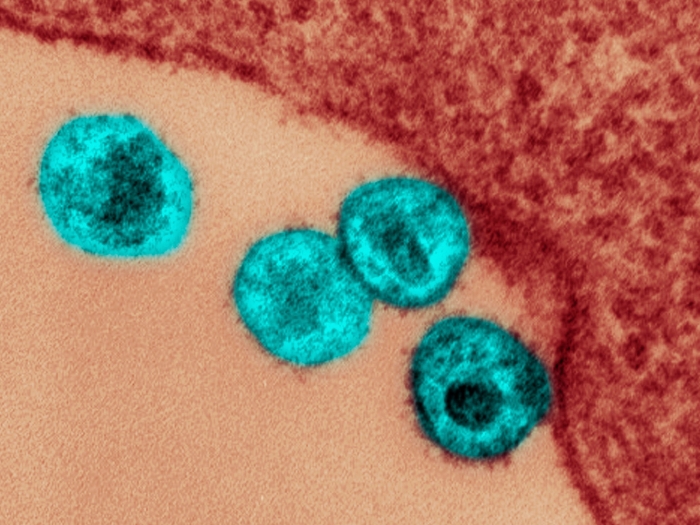

In addition, the researchers used 16S rRNA gene sequencing, a technique that identifies bacteria present in a sample via their DNA signature, in the mice models and human tissues to identify which gut bacteria fueled their hypothesis.

"The traditional thing to do in a microbiology lab is take a sample and try to grow bacteria from it in the lab under particular conditions and see what you get," Singer says. "We know, though, that there are many bacteria that are important in the gut microbiome but that don't grow in the traditional methods.

"We can take a sample and isolate the DNA from it and sequence the 16S rRNA gene. Then we can compare the sequences of those genes to a database of known bacteria and identify many more bacteria in the tissue, instead of relying on what grows in a culture."

Results supported the hunch: Researchers found that gut bacteria present in the brains of the mice five days after surviving sepsis — but gone by 14 days after the infection — were associated with levels of S100A8, a marker of neuroinflammation.

Singer notes that while the human tissue analysis was a small cohort, the research team noticed distinct differences between patients who died of sepsis and those who died of noninfectious causes.

"Anytime someone dies, bacteria grow out of control because the immune system is not keeping the bacteria in the body in check," Singer says. "But we found that the bacteria we isolated from patients that died of sepsis were quite different from the run-of-the-mill bacteria that sit in the body after a person dies — and did appear to be associated with neuroinflammation in the brain."

As was observed in mice, the gut bacteria detected in brains of patients who died of sepsis correlated with the S100A8 inflammation marker.

Implications for real-life care

The study's conclusion: Sepsis causes gut bacteria to locate in the brain for several days and ultimately resolves in the weeks after the onset of illness.

Because the gut bacteria were present in the brains of both the mice and humans who died of sepsis — and those bacteria were associated with the marker for inflammation of the brain — the findings indicate gut bacteria do appear to play a role in brain dysfunction after sepsis.

"The larger question raised by this study is: Is there anything we can do to intervene and change the consequences of critical illness for survivors?" Singer says. "Results from the microbiome and lung inflammation study and this one suggest that one, there are bacteria that are directly involved in organ injury, and two, the bacteria that have disseminated to different organs during sepsis are not always the bacteria that the clinical laboratory identifies in the blood culture and that are the target of your antibiotic treatment."

The results could have implications for providing care.

Singer notes the study also suggests, although additional research would be needed, that treating gut bacteria could help avoid or reduce brain dysfunction.

"Giving patients oral antibiotics to remove those bacteria in the gut may potentially reduce long-term effects of critical illness," Singer says.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!