A new understanding of the interaction among multidrug-resistant bacteria, and how antibiotics affect them, could lead to better infection prevention.

7:00 AM

Author |

What's worse than exposure to a microbe modern antibiotics can't kill?

Exposure to more than one — because they may work together to cause an infection, new research suggests.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

And trying different antibiotics to control one such "superbug" may only encourage others lurking nearby, according to data from hundreds of nursing home patients and a University of Michigan research team.

In fact, researchers say it is time to think about such bacteria as members of an antibiotic-resistant ecosystem in health care environments — not as single species that act and respond alone.

Of the 234 frail elderly patients in the study, 40 percent had more than one multidrug-resistant organism, or MDRO, living on their bodies. Patients who had specific pairs of MDROs were more likely to develop a urinary tract infection involving an MDRO.

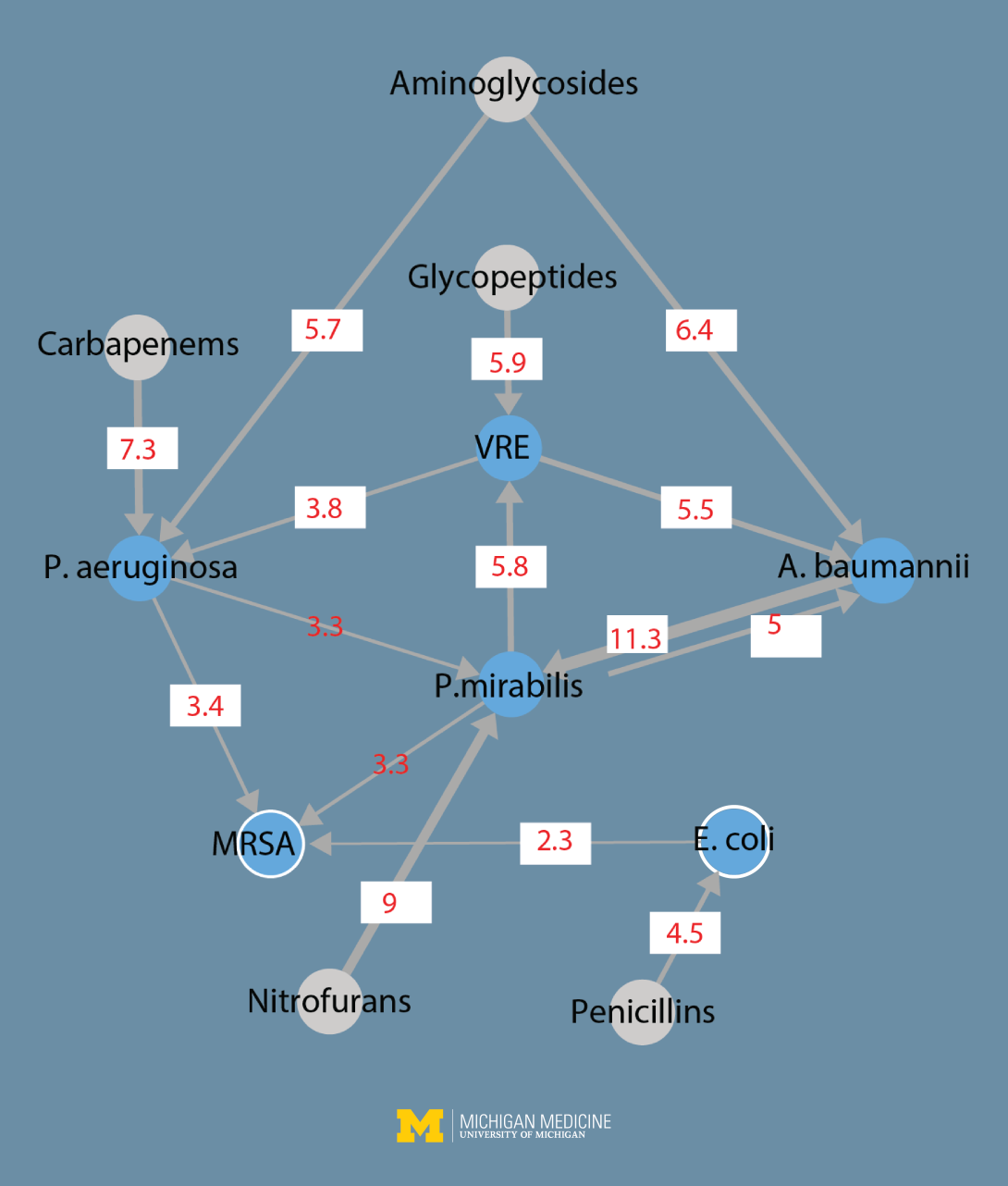

The researchers created a map of interactions among bacteria and classes of antibiotics, which they published with their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Eventually, such mapping could help health care providers. For instance, they could treat a patient with a specific antibiotic not only because of its ability to kill one MDRO, but also for its potential downstream impact on other MDROs on the patient or lurking nearby.

But that will take time, and more research in the laboratory and in health care facilities, says researcher Evan Snitkin, Ph.D., a systems biologist at the U-M Medical School Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

In the meantime, the team suggests their findings can give health care providers and patients even more reason to avoid using nonessential antibiotics — as "superbugs" evolve in response to them.

"Reducing the overall burden of antibiotic-resistant organisms in health care facilities will require strategies that consider both the intended and unintended consequences of antibiotic treatment decisions," says Snitkin.

Reducing the overall burden of antibiotic-resistant organisms in health care facilities will require strategies that consider both the intended and unintended consequences of antibiotic treatment decisions.Evan Snitkin, Ph.D.

An ecosystem of resistance

The researchers used detailed data from a long-term study of nursing home patients led by U-M geriatrician Lona Mody, M.D., M.Sc., who studies infection transmission and prevention in nursing homes. The team also included Betsy Foxman, Ph.D., a longtime researcher in the epidemiology of antibiotic resistance and urinary tract infections at the U-M School of Public Health.

Nearly two-thirds of the patients studied were treated with one or more of 50 different antibiotics during the study period. All the patients used a urinary catheter to empty their bladders for at least three days during the study period. This allowed the researchers to look at patterns of urinary tract infections, which among nursing home and hospital patients often arise from bacteria entering the bladder along a catheter.

The findings showed that colonization of such patients' skin, noses and throats with common MDROs was not random.

"We observed a complex network of interactions, with acquisition of each of six different MDRO species being influenced by different sets of antibiotics, and primary MDRO colonization in turn increasing the risk of acquisition and infection by other MDROs," says lead author Joyce Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Snitkin's lab who led the analysis.

Colonization with one MDRO increased the risk of acquiring other MDROs but not all others. It was as if they were interacting very specifically with other species. And treatment of a patient with any given antibiotic increased his or her chances of being colonized with an MDRO, which in turn altered his or her risk of becoming colonized with another MDRO later.

Superbug cooperation

The researchers focused on two of the most dangerous MDROs — vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) — as well as four Gram-negative bacteria that have evolved resistance to two powerful antibiotics.

SEE ALSO: Study Shows How Pneumonia-Causing Superbug Invades

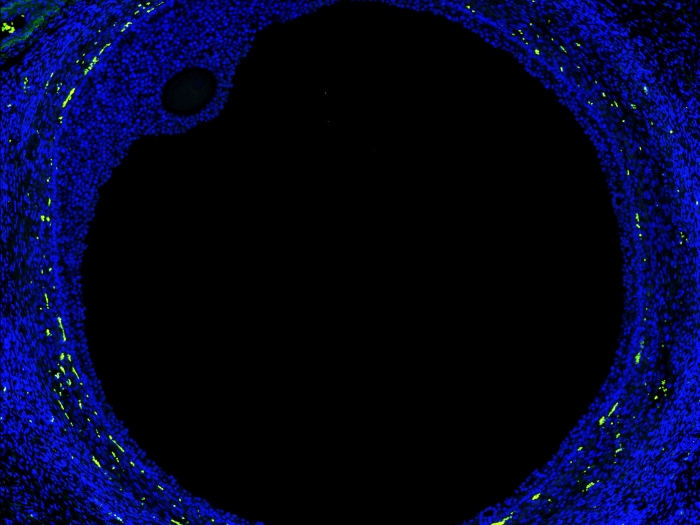

One of the four, Proteus mirabilis, causes many catheter-associated UTIs and can form biofilms that involve many bacteria. It's known to release a compound called urease, which acts as a means of communication among bacteria. The other three species studied were Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

These species are known to cause many infections in hospitals, which have poured major effort into fighting them and preventing their spread.

But, says Snitkin, "a lot of the attention in infection prevention is paid to large academic hospitals — but this is a fruitless endeavor if you're not controlling the same organisms in all the connected health care facilities and nursing homes."

"We need to understand what clinical practices drive the spread of MDROs in health care facilities, and counterintuitively, it appears that a key factor is the use of certain antibiotics used against an individual organism that may impact other circulating organisms."

In short, every nursing home and likely every hospital in America is home to a natural experiment in the evolution of bacteria strains to become resistant to drugs and to survive on a host patient or travel among hosts.

Advanced DNA sequencing techniques could someday help those working to combat superbugs, Snitkin says. These tools, which he and his colleagues have used in their research labs for a decade, help pinpoint which strains of bacteria are present and how they're evolving.

That, combined with knowledge about how MDRO strains interact with one another and how specific antibiotics affect them, could help steer doctors' decisions.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by a pilot grant from the U-M Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, a research division of the U-M Geriatrics Center funded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

Vote for this research in STAT Madness 2018, a bracket-style competition for the best ideas in science and medicine, sponsored by STAT News.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!