How a recently identified defensive compound called itaconate tricks the bacteria behind tuberculosis.

3:30 PM

Author |

Close to 1.8 billion people worldwide are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the common and occasionally deadly bacterium that causes millions of cases of tuberculosis each year. The bacteria, having coevolved with humans over millennia, have devised ways of hijacking nutrients from its human host for its own benefit. Humans have equally complex ways of fighting back.

In a new study appearing in the journal Science, a team led by Michigan Medicine researchers working with collaborators at Harvard, has discovered a specific mechanism by which a "weapon" used by the immune system, called itaconate, targets Mtb.

Researchers only recently discovered that itaconate is produced in large amounts by the immune system when under attack. So far, just how itaconate disarms disease-causing bacteria has been somewhat of a mystery.

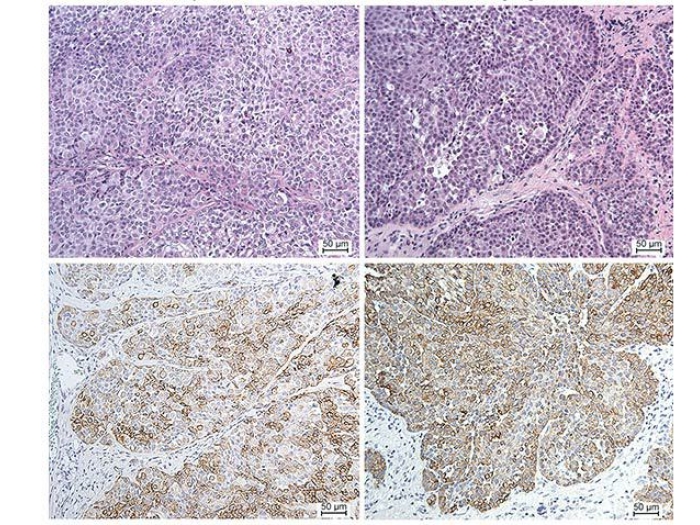

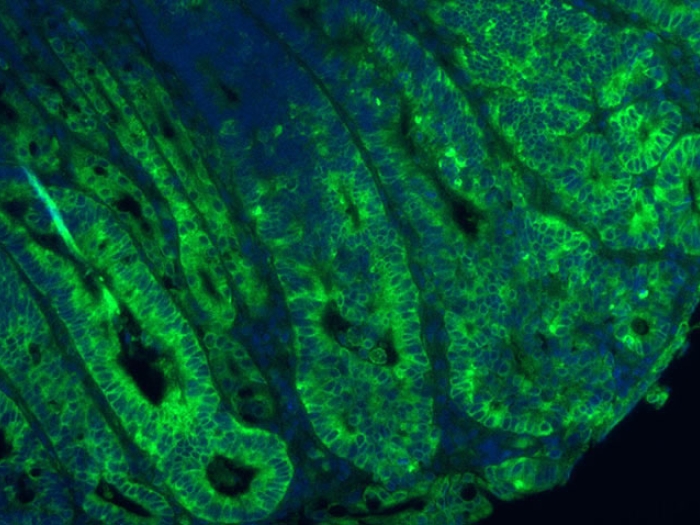

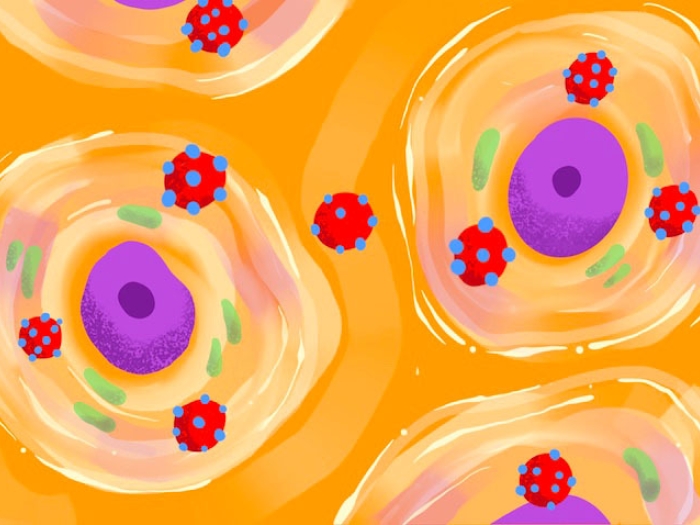

Mtb hides inside human immune cells, using cholesterol for the energy needed to grow and proliferate. During this process, the bacteria produce a toxic intermediate called propionate, which it must get rid of. One strategy for propionate disposal relies on vitamin B12 derived from the human host. "B12 is a very interesting vitamin in that it is required in very low concentrations by our cells, perhaps the lowest of any vitamin, yet it's essential for life," says Ruma Banerjee, Ph.D., a professor of biological chemistry at the U-M Medical School and senior author of the new paper.

A biologically active form of the vitamin, called coenzyme B12, was discovered more than 60 years ago and is involved in cellular metabolism. Coenzyme B12 allows very complex chemistry to occur in bacteria and human cells because it releases radicals, or unpaired electrons, that enable otherwise very challenging chemical reactions. Typically, radicals are highly unstable and therefore short-lived. "In the body, free radicals cause cellular and DNA damage because they are very reactive," says Banerjee. The pair of radicals (called a biradical) generated by coenzyme B12 is so reactive, she explains, that it raises the question as to how the enzyme is able to contain and use it.

The team was able to show that an activated form of itaconate, called itaconyl-CoA, blocks the B12-dependent pathway in the tuberculosis bacterium, preventing it from using propionate to grow. It does so by acting as a decoy, "tricking the B12-dependent enzyme into using itaconyl-CoA as a substrate, which then leads one of the radicals to commit suicide," says Banerjee.

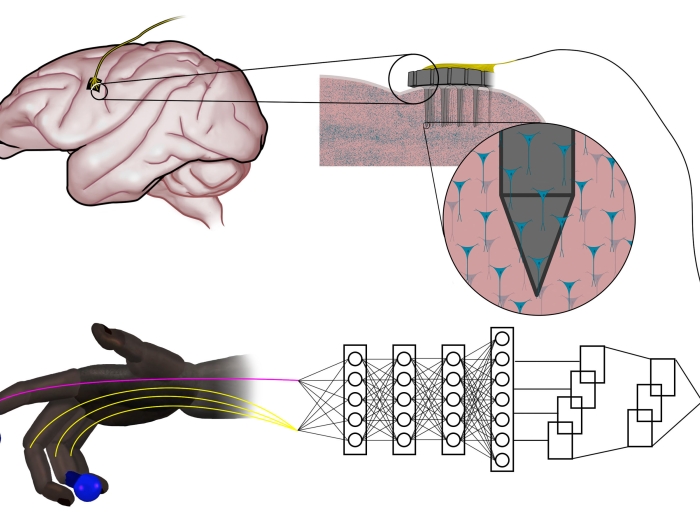

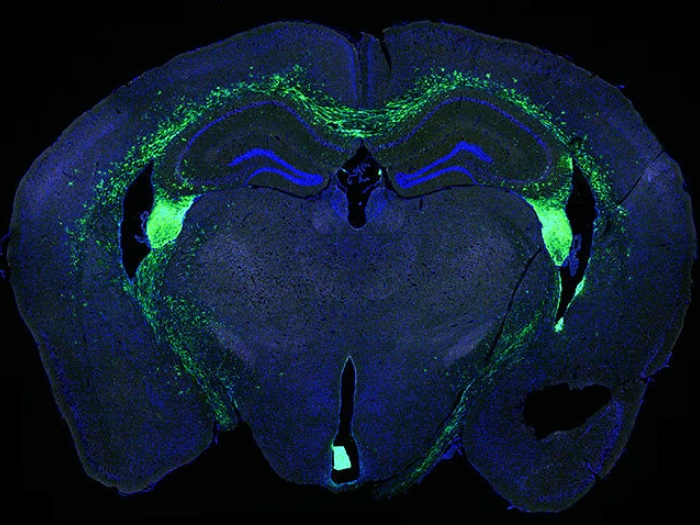

What's more, the itaconyl-CoA/coenzyme B12 reaction produced a stable biradical that lingered for more than an hour instead of disappearing rapidly. This enabled lead author Markus Ruetz, Ph.D., of the department of biological chemistry in collaboration with the structural biology group led by Markos Koutmos, Ph.D., of the department of chemistry at U-M to grow crystals of the enzyme containing the biradical and obtain its 3D structure. "This is the first time anyone has seen this biradical," says Ruetz. "Understanding how an enzyme can harness such reactivity can perhaps allow us to repurpose the method and could be invaluable in terms of chemistry," added Koutmos.

This new observation could also begin to explain why 3% to 5% of the human population carries a mutated gene. "People with a mutation in the CLYBL gene have no obvious ill effects except their B12 levels are slightly lower," says Banerjee, who speculates that this could confer an advantage against infection.

Paper cited: "Itaconyl-CoA forms a stable biradical in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase and derails its activity and repair," Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.aay0934

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!