With the help of a new human embryonic stem cell line, researchers make initial strides toward treatment for the genetic mutation.

7:00 AM

Author |

Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability and autism and poses a significant burden to affected families. The syndrome gets its name because — under a microscope — part of the X chromosome in affected individuals appears broken or fragile.

Because males have only one X chromosome, as opposed to two in females, they are typically more severely affected by the Fragile X mutation. While there is no cure, researchers have been studying the gene responsible for Fragile X, called FMR1, to find a viable treatment.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Genes contain the instructions to make proteins. A genetic mutation is like an instruction manual full of gibberish instead of recognizable words.

A dangerous repeat

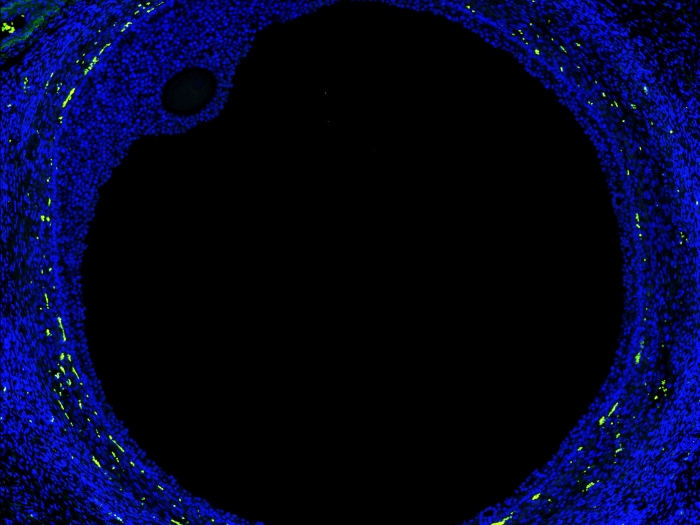

In the case of Fragile X, a "word" made up of three nucleotides, CGG, is repeated hundreds of times in the FMR1 gene instead of the normal 25 to 40 repeats. This high repetition deactivates the gene through a process called methylation, and it leads to a loss of the protein FMRP. That lack of FMRP leads to seizures, anxiety, learning difficulties and other Fragile X symptoms.

Michigan Medicine researchers have been working with human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) donated by a couple with the Fragile X mutation to try to reactivate production of the protein.

The stem cell line itself, developed by Gary Smith, Ph.D., a professor of molecular and integrative physiology and of obstetrics and gynecology and the director of Michigan's MStem Cell Laboratories, is a critical development for the field of Fragile X research.

SEE ALSO: A Drug Makes Stem Cells 'Embryonic' Again

"There are many reasons why we do these experiments in human embryonic stem cells," says senior researcher Peter Todd, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of neurology. "First, humans and mice are not the same, especially when you're talking about autism and intellectual disability. Additionally, the way the gene turns off doesn't happen in mice, so we can't institute the state the disease occurs in in order to correct it."

With the new hESC line, the researchers saw that as the cells grew, the gene was initially turned on and transcribing at near normal levels. However, they stopped making RNA over time. Todd suspects that making RNA with a large repeat is somehow unhealthy for the cells and that the cells that turned off the gene survived.

The question remained: What happens if the troublesome repeat was turned back on? The team used a powerful cellular tool to target the repeat and observe what would happen to the protein-making process.

Humans and mice are not the same, especially when you're talking about autism and intellectual disability.Peter Todd, M.D., Ph.D.

An attempt at reactivation

CRISPR-Cas9 has become popular recently for its ability to edit DNA. However, the team used a slightly different form, CRISPR-dCas9, to deliver a special activator protein specifically to the site of the abnormally large repeat on the FMR1 gene. Once there, the attached protein was used to reactivate the gene and get it to transcribe once more.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

"The fact that we can see that effect even at large repeat lengths that are fully silenced suggests that dCas9 can recognize the sequence," Todd says.

Theoretically, this should be enough to generate FMRP. And in normal cells, researchers saw an increase in the protein. However, "at 800 to 900 repeats, we were getting activation at the transcription level but not very much protein," Todd says. Possible explanations for this discrepancy range from incomplete delivery of the activator to cells to the size of the repeat itself. Despite this, the study provides new hope for researchers by demonstrating that FMR1 can be targeted and reactivated.

SEE ALSO: Turn a Cell into Any Other Kind of Cell, No Magic Wand Required

Since the goal is to make enough FMRP, the group plans to compare this approach to others with different cell lines, repeat sizes and degrees of methylation. The researchers say even small successes with reducing methylation, increasing transcription and increasing the production of FMRP could result in reduced symptoms for patients.

Their paper is published in Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!