An enzyme’s newly discovered ability to spur the body to prevent or repair acute liver injury in mice could be harnessed as a therapy or used as a biomarker.

7:00 AM

Author |

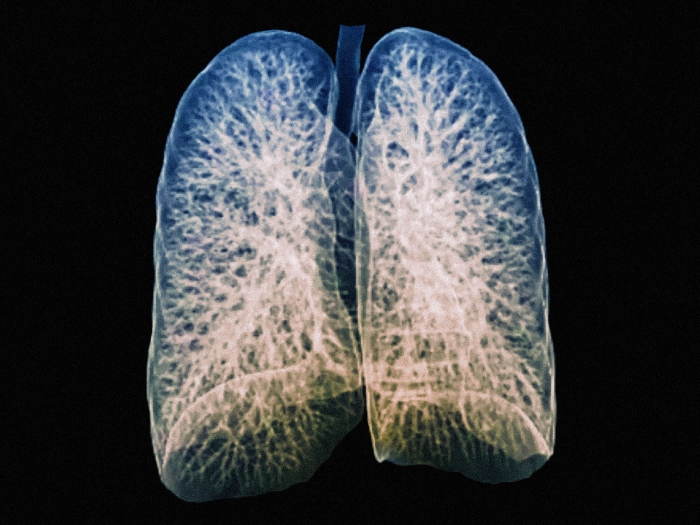

On a normal day, the cells of a human liver do what they do best — make key blood proteins, clear toxins from the blood and send their remains down the digestive tract in a stream of bile.

But when something badly injures enough of these cells — such as with an overdose of pain medicine — this vital work can come to a screeching halt. With few good treatment options available, more than 2,000 Americans develop acute liver failure each year.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Now, new research in mice points to a potential way to better monitor the health of patients who have suffered the damage, treat the damage and even prevent the damage from happening.

It's very exciting since it offers a potential pathway to develop new treatments.Bishr Omary, M.D., Ph.D.

In a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team from the University of Michigan describe how a protein involved in one of the liver's most basic functions also sounds the alarm when liver cells get hurt.

That alarm, and the help that it summons from the immune system, can help protect the liver from further damage, the researchers report. It can even spur the repair of a damaged liver after injury, says Bishr Omary, M.D., Ph.D., who led the research team.

Unexpected function

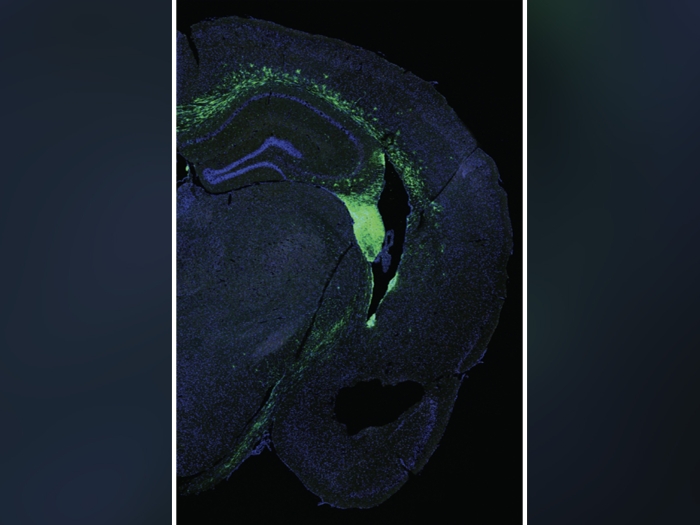

Working with a team of U-M colleagues from many fields, Omary and former postdoctoral fellow Min-Jung Park, Ph.D., discovered an unexpected function for the enzyme CPS1, short for carbamoyl phosphate synthetase-1.

Normally, CPS1 plays a key role in breaking down ammonia, a waste product the body needs to get rid of. It does this in the mitochondria of the major cells of the liver, called hepatocytes.

SEE ALSO: Many Popular Dietary Supplements Can Yield Dangerous Liver Results

A few years ago, Omary and his team discovered CPS1 in an unexpected place: the blood of animals and humans with acute liver injury. They showed that the amount of CPS1 in the blood served as an indicator of the extent of the damage — but also found that it left the blood quickly. That made it a potential early marker for recovery from liver injury.

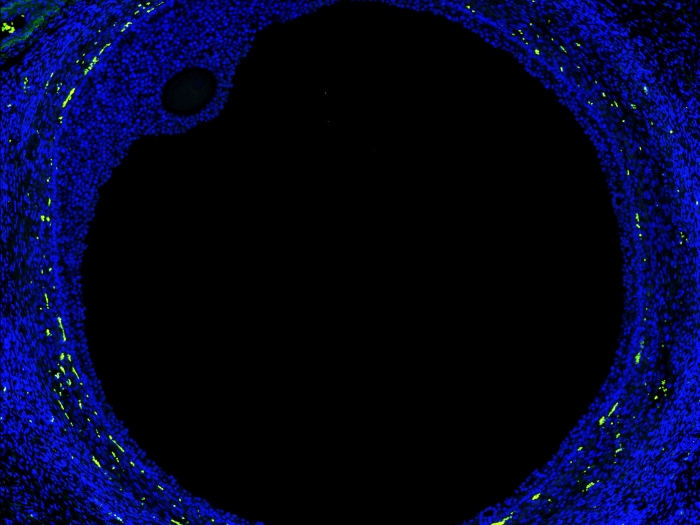

In the new paper, they report that CPS1 is normally released into bile but ends up in blood upon acute liver injury. They were surprised to learn that CPS1 had reached the inside of white blood cells called monocytes. There, they found, it performs a good deed.

"CPS1 that is cleared from blood reprograms monocytes to become anti-inflammatory and move to the liver," says Omary, a professor in the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology and the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the U-M Medical School. "This cytokine-like function, which is entirely unrelated to its usual enzymatic function, provides a mechanism for the protective effect we observed.

"It's very exciting since it offers a potential pathway to develop new treatments," Omary says.

Painstaking work

Park, now a research scientist in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Chonnam National University in South Korea, led the painstaking work of studying CPS1 in the blood, bone marrow, liver and bile of mice and then working to increase its levels in the blood by injecting mice with an extra supply she generated in the lab.

The researchers gave this exogenous CPS1 to mice before they exposed them to acetaminophen — the pain reliever in Tylenol, the over-the-counter medication that millions of people take. The medication holds the potential to damage the liver in high doses and in combination with other substances.

Even when the mice received doses high enough to cause acute injury, those that received added CPS1 beforehand did not suffer major liver damage.

Signs of recovery

When the researchers injected CPS1 into mice after they received the high dose of acetaminophen, the animals' livers showed significant signs of recovery.

"The amount of CPS1 released to blood naturally is not sufficient to cope with injury, which is why the boost becomes very helpful," says Park. "In contrast, if too much is spilled to blood by the liver, then this means too many liver cells have died to have a chance to recover."

SEE ALSO: Screen Saver: Why Too Many Patients Get Liver Tests They Don't Need

Omary notes that since CPS1 is a fairly large protein, any effort to use and understand its therapeutic capacity might be improved by determining which of its components are most important for triggering the anti-inflammatory response.

He and his team are working to assess exactly how it works in mice and to determine if it ultimately can be used as a therapeutic in humans. However, he cautions that significantly more work will be needed to determine the feasibility of its human use.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (DK47918, TR002240 and DK34933) including a Postdoctoral Translational Scholars Program award to Park through the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research.

The University of Michigan has applied for patents on the use of CPS1 as an anti-inflammatory biologic, as well as for its potential utility as a biomarker to predict the severity of acute liver failure.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!