Enzyme is behind the breakdown of the protective mucus barrier in the gut

5:00 AM

Author |

A new study published in Nature has found that a single sulfatase contributes to the degradation of mucus that protects the intestinal lining, potentially leading to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer.

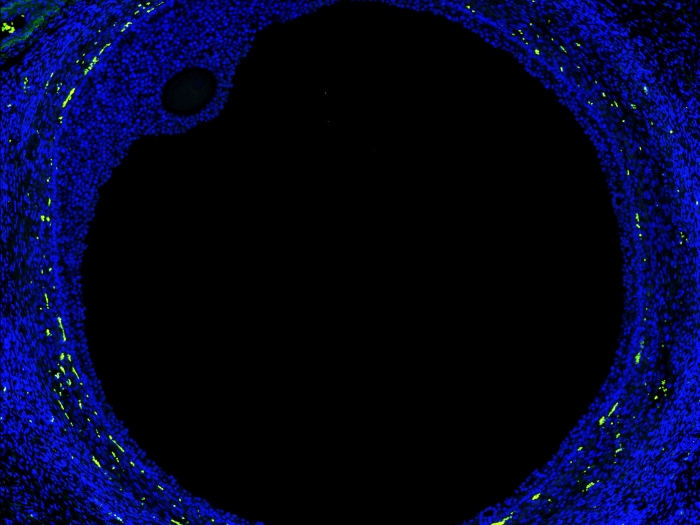

The human gut microbiota significantly impacts several aspects of intestinal health and disease, including inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. In the colon, secreted mucus creates a barrier that separates gut microorganisms from the lining of the intestine, preventing close contact that can lead to these conditions.

Some gut bacteria are able to use mucin glycoproteins, the main mucus component, as a nutrient source. However, it remains unclear which bacterial enzymes initiate degradation of the complex O-glycans found in mucins.

Despite the critical roles of sulfatases in many biological processes, including diseases, the researchers from a group of universities including the University of Liverpool, University of Gothenburg, and the University of Michigan aimed to address the significant knowledge gap regarding their specificity and mechanisms.

A major component of colonic mucus is mucin 2, a glycoprotein. Mucin glycosylation is variable along the gastrointestinal tract, with an increase in sulfation in the colon, especially in the distal colon.

To degrade the complex O-glycans found in mucins, some human gut bacteria have evolved complex arsenals of degradative enzymes that include sulfatases.

By characterizing the activity of 12 different sulfatases, researchers were able to show that sulfatases are essential to the utilization of distal colonic mucin O-glycans by the human gut symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron.

The study reveals that B. thetaiotaomicron has a robust ability to grow on highly sulfated colonic mucin and that it possesses sulfatases capable of removing sulfate groups in all contexts in which they are known to occur in mucin. Surprisingly, researchers found that a single key sulfatase is disproportionately important for growth on colonic mucin O-glycans.

The findings support a critical role for active sulfatases in both normal colonization and inflammation.

Given that mucin glycan structures may vary between mammalian hosts, these critical steps may eventually need to be validated in humans.

These findings will inform future research into blocking this complex enzyme pathway and potentially inhibiting mucin-degrading activities in bacteria that contribute to diseases such as IBD.

Paper cited: "A single sulfatase is required to access colonic mucin by a gut bacterium," Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03967-5

Adapted from a press release from the University of Liverpool, UK.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!