Study suggests that the overexpression of cochlear neurotrophin-3 can help prevent the loss of hearing.

5:00 AM

Author |

Age-related hearing loss is a prevalent disorder that holds the power to diminish the quality of life for those dealing with the condition. It's also a key contributor to things like social isolation, depression and dementia, however no therapies currently exist to prevent its progression.

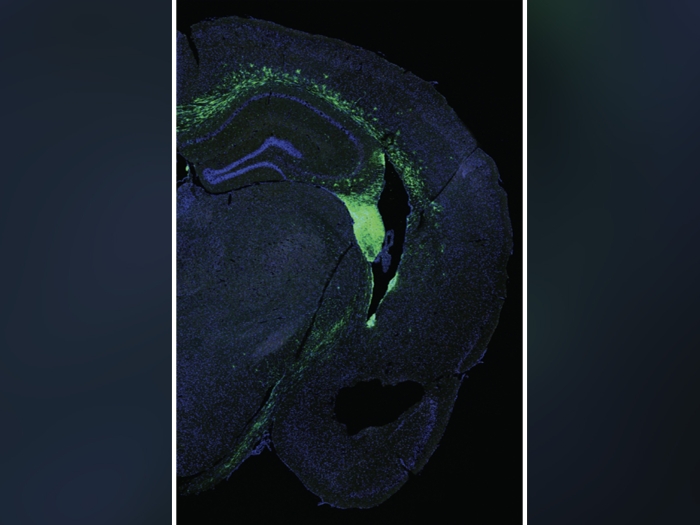

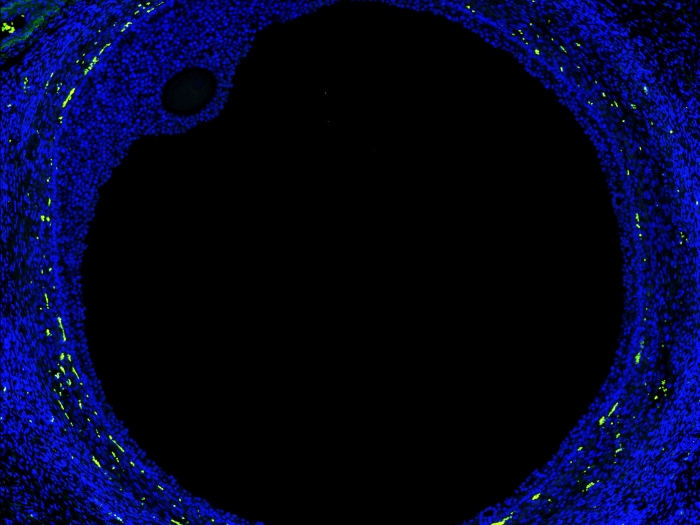

Gabriel Corfas, Ph.D., who serves as the director of Michigan Medicine's Kresge Hearing Research Institute, says that one of the first events in "cochlear aging" that leads to hearing loss is the breakdown of synapses between inner hair cells, or IHCs, and spiral ganglion neurons, or SGNs.

"In many cases, this phenomenon called 'IHC synaptopathy' precedes neuronal and hair cell loss," said Corfas. "Ultimately, this means that the connections between these cells is lost, and important parts of auditory information are not sent to the brain."

This notion inspired Corfas and a team of hearing researchers to explore if age-related IHC synaptopathy can somehow be stopped, thus preventing age-related hearing loss. Their results were recently published in Aging Cell.

"We tested the effects of cochlear overexpression of neurotrophin-3, or Ntf3, in middle-aged mice," said Corfas. "We were able to demonstrate that we can stop the loss of these synapses by increasing the amount of this neurotrophic factor in middle-aged mice that were already experiencing mild, but significant, hearing loss."

The team achieved this by modifying the mouse genome, allowing them to regulate when and in which cells the Ntf3 gene was expressed.

"This technique is called 'inducible transgenesis,'" said Corfas. "Basically, we were able to make certain cells in the inner ears of the mice express higher levels of the Ntf3 neurotropic factor after administering a drug that activates the transgene."

Corfas adds that during the aging process, the levels of neurotrophin-3 within the inner ear decrease. However, the team of researchers was able to successfully bring the levels of Ntf3 within the aged mice to the same levels as the young mice.

"Other studies in our laboratory showed that the number of IHC synapses correlate with the processing of auditory information and therefore influences the ability to hear in noisy environments," said Corfas. "The more synapses there are, the better the mice can hear. Our findings indicate that preventing age-related IHC synaptopathy should improve overall hearing as we age, as well as hearing in noisy environments."

Corfas says that he hopes this research will lay the foundation for not only delaying age-related hearing loss in humans, but also helping them hear better in (and after experiencing) loud places.

And the team's findings reveal even larger implications.

"Our study suggests that factors associated with regulating synaptogenesis during development can possibly prevent age-related synaptopathy in the brain. This could someday be useful in preventing various disorders related to the central nervous system."

Live your healthiest life: Get tips from top experts weekly. Subscribe to the Michigan Health blog newsletter

Headlines from the frontlines: The power of scientific discovery harnessed and delivered to your inbox every week. Subscribe to the Michigan Health Lab blog newsletter

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

Paper cited: "Cochlear Neurotrophin-3 overexpression at mid-life prevents age-related inner hair cell synaptopathy and slows age-related hearing loss," Aging Cell . DOI: 10.1111/acel.13708

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!