Innovative device ensures doctors obtain adequate fluid samples from the eye, helping with diagnosis and individualized treatment plans for patients.

12:34 PM

Author |

When a patient becomes sick, a clinician can use a needle to get a fluid sample from almost any organ in the body.

A molecular analysis of this fluid helps clinicians determine a diagnosis and create the most specific and effective treatment plan for the patient, a customized approach known as precision medicine.

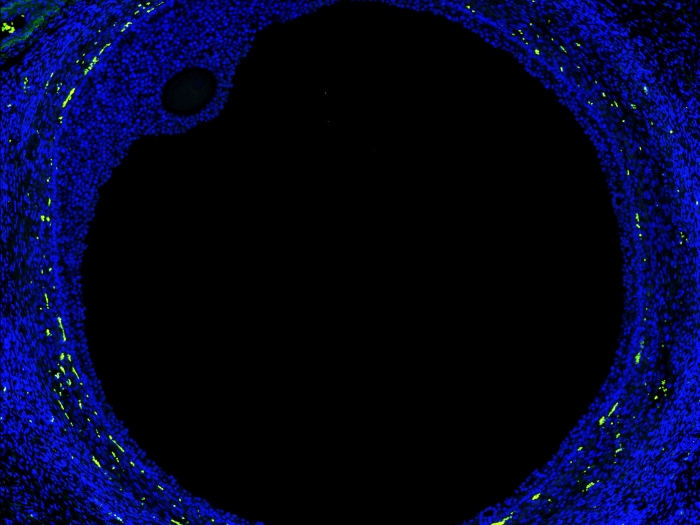

Although the eyes contain a gel-like fluid that can be readily sampled with a needle, precision medicine for eyes diseases is lacking.

That's why Thomas Gardner, M.D., M.S., an ophthalmologist at the University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center, and Jeffrey Sundstrom, M.D., Ph.D., an ophthalmologist at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, are working together to make a safe device that can be used in the clinic room and ensures adequate fluid samples are obtained every time.

The eyes are one organ that don't have routine molecular diagnosis tests, and Gardner warns this can have grave consequences in diagnosing and treating potentially vision-threatening conditions for patients.

"Many clinicians are hesitant to put a needle in someone's eye without a strong indication that something is wrong, and that's normally when there's an infection," he says. "And for those that do get a diagnostic test done, it's often difficult to get an adequate sample."

This leaves ophthalmologists to make diagnoses and provide treatment plans based on their best, educated guesses, which Gardner says, is unacceptable.

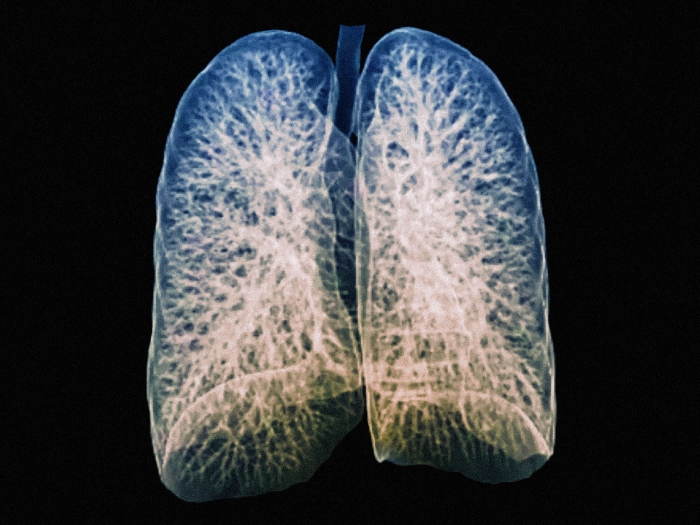

Why this matters

Many eye diseases, like age-related macular degeneration, a degenerative eye disease that damages the retina, and diabetic retinopathy, the damage of nerve cells and blood vessels in the eyes that can lead to blindness, look similar when examined by an ophthalmologist.

"Inflammatory conditions in the eye look similar," Gardner says. "And although infection has specific features that make it identifiable, these features aren't unique to any particular infection."

Because treatments are non-specific for many inflammatory eye conditions, a patient might just get steroids as a treatment plan to try and reduce the inflammation.

Regular needles don't work all the time, and we need them to work all the time.Thomas Gardner, M.D., M.S.

Eye care is today where cancer care used to be a few decades ago, according to Gardner. Many cancers used to be treated by chemotherapy or radiation that affected the whole body. Now, specific mutations in the body's tissue can be identified and classified so medication can be tailored to the mutation responsible for the cancer.

In this regard, precision medicine can be more effective and carry a lower possibility of negative consequences to the patient's overall health.

The 'Mini-Vit'

Currently, there isn't any standard process for collecting vitreous, or the eye's gel-like, fluid samples. Often, they're retrieved by a retina surgeon in the operating room from patients that need surgery, because it's easiest to get an adequate sample that way.

However, surgery can be expensive, and Gardner says the threshold for collecting a fluid sample for analysis shouldn't be getting a patient in the operating room.

One of the major problems is that the needle used to get a good sample doesn't always work because the fluid is gelatinous and clogs it.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

To make acquiring a sample easier, Gardner and Sunstrom have worked with Lauro Ojeda, M.S., a research scientist in the University of Michigan's engineering department, to develop a handheld, disposable device specifically designed for getting a substantial sample. The device, called the Mini-Vit, contains a needle inside a larger needle that can cut the gelatinous fluid – the culprit of an inadequate sample.

"Regular needles don't work all the time, and we need them to work all the time," Gardner says.

The project started with funds from Fast Forward Medical Innovation's Kickstart Program and is now funded by the Coulter Translational Research Partnership Program and the Taubman Institute.

These funds will also be used to create a standard process for analyzing the fluid at the molecular level, referred to as "oculomics".

The team is also working with Alexei Nesvizhskii, Ph.D., a pathologist at Michigan Medicine and Christopher Gates, M.S., the managing director of Bioinformatics Core, to create a repository of patient samples and develop new computational tools clinicians can use to compare to a large database of samples. They collaborate on the data analysis with Venkatesha Basrur, Ph.D., Felipe da Veiga Leprevost, Ph.D., and Jingqun Ma, Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, as well as Sarah Weber, B.S. and Yuanjun Zhao, M.D., Ph.D. at Penn State.

This repository will help clinicians identify or create the most specific and effective treatment plan for a given patient, or group of patients.

"These processes of collecting, analyzing and comparing patient samples could significantly advance Kellogg Eye Center's approach to vision-threatening conditions, as well as provide more treatment options for patients that may have previously thought there weren't any," Gardner says.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!