Key differences seen in brains of patients who responded to exposure-based therapy or stress-reduction therapy; new study seeks children and teens for further research

10:10 AM

Author |

New research could improve the odds that people with obsessive-compulsive disorder will receive a therapy that really works for them – something that eludes more than a third of those who currently get OCD treatment.

The study, performed at the University of Michigan, suggests the possibility of predicting which of two types of therapy will help teens and adults with OCD: One that exposes them to the specific subject of their obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, or one that focuses on general stress reduction and a problem solving approach.

While the researchers caution that it's too early for their work to be used by patients and mental health therapists, they're planning and conducting further studies that will test the framework and see if it also applies to children with OCD or obsessive tendencies.

Comparing therapies for OCD

The new study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, examines advanced brain scans of 87 teens and adults with moderate to severe OCD who were randomly assigned 12 weeks of one of the two types of therapy.

The researchers found that in general, both types of therapy reduced the symptoms that participants experienced. The approach known as 'exposure therapy', a form of cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, was more effective and reduced symptoms more as time went on, compared with stress-management therapy, also known as SMT.

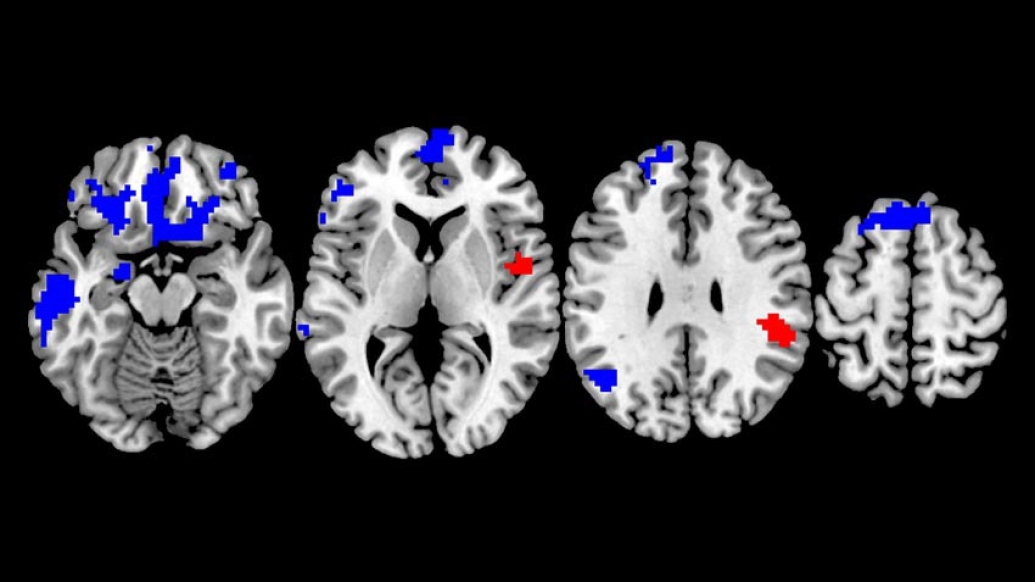

But when the researchers looked back at the brain scans taken before the patients began therapy, and linked them to individual treatment response, they found striking patterns.

SEE ALSO: Stuck in a Loop of 'Wrongness': Brain Study Shows Roots of OCD

The brain scans were taken while patients performed a simple cognitive task and responded to a small monetary reward if they did the task correctly.

Those who started out with more activation in brain circuits for processing cognitive demands and reward during the tests were more likely to respond to CBT – but those who started out with less activation in those same areas during the same tests were more likely to respond well to SMT.

"We found that the more OCD-specific form of therapy, the one based on exposure to the focus of obsession and compulsion, was better for relieving symptoms, which in itself is a valuable finding from this head-to-head randomized comparison of two treatment options," says Stephan Taylor, M.D., the study's senior author and a professor of psychiatry at Michigan Medicine, U-M's academic medical center. "But when we looked at the brain to see what was behind that response, we found that the more strength patients had in certain brain areas were linked to a greater chance of responding to exposure-based CBT."

Key brain regions involved in studying OCD

The brain regions and circuits that had the strongest links to treatment have already been identified as important to OCD – and have even been targets for treatment with an emerging therapy called transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Our research shows that different brains respond to different treatments, and if we can build on this knowledge we could move toward a more precision-medicine approach for OCD.Kate Fitzgerald, M.D.

Specifically, stronger activity in the circuit called the cinguloopercular network during the cognitive task, and stronger activity in the orbitostriato-thalamic network when the reward was at stake, was associated with better response to exposure-based CBT. But lower activity in both regions was associated with better response to the stress-reduction SMT. The effects didn't vary across age groups.

"These findings speak to a mechanism for therapy's effects, because the brain regions associated with those effects overlap substantially with those implicated previously in this disorder," says Luke Norman, Ph.D., who led the work as a U-M neuroscience postdoctoral fellow and is now a scientist at the National Institutes of Health. "This suggests we need to draw upon the most-affected networks during therapy itself, but further research is needed to confirm."

The brain scans were done while patients underwent a test that required them to correctly pick the correct letter out of a display, and offered a potential monetary reward if they performed the task correctly. This measured both their ability to exert control over their cognitive processes in picking out the right letter, and the extent to which the promise of a reward motivated them.

One of the areas most linked to CBT treatment response was the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC). Past research has already linked it to OCD and treatment response in general, and it's thought to play a key role in self-regulation of response to OCD triggers. Previously, the U-M team had shown that in general, people with OCD tend to have reduced activation in the rACC when asked to perform tasks that involve cognitive control.

Among those who responded best to CBT, the researchers saw stronger pre-treatment activation in areas of the brain associated with learning how to extinguish fear-based responses to something that has caused fear in the past. Because exposure therapy for OCD involves facing the thing or situation that provokes obsessive and fearful responses, having a stronger ability to be motivated by rewards might help someone stick with therapy despite having to face their triggers.

Personalizing OCD treatment

The findings suggest a path to personalizing the choice of therapy not by doing brain scans on everyone with OCD – which would be impractical – but by using everyday tests that measure the kinds of characteristics that might predict better success with one therapy or the other.

Kate Fitzgerald, M.D., a pediatric OCD specialist at Michigan Medicine who is co-senior author of the paper and leads multiple studies of OCD therapy for children and adolescents, explains that easily administered behavioral tests could be developed to help therapists recommend CBT to those who have the most cognitive control and reward responsiveness, and SMT to those who would benefit most from being taught to relax and use problem-solving techniques to improve their response to stressors.

SEE ALSO: How to Recognize Your Child Might Have OCD

But computer-based brain-training exercises that can strengthen these tendencies, and rewards for exposing oneself to the thing or action that triggers OCD symptoms, may hold the potential to improve therapy response, she says.

"This kind of research may help inform efforts to do cognitive control training and ramp up the circuits that help patients overcome conflict between obsessive fears and insight that these fears don't make sense so that patients can dismiss the fear as improbable, rather than trying to make it go away with compulsive behaviors," she says. "Our research shows that different brains respond to different treatments, and if we can build on this knowledge we could move toward a more precision-medicine approach for OCD."

In children and teens, whose brains are still maturing, there's an especially good chance of helping them improve their brains' control functions.

New research to advance OCD understanding

Fitzgerald and her team are currently recruiting young people with diagnosed OCD, and OCD-like tendencies, for a clinical trial that provides CBT and includes brain scanning before and after therapy.

Since OCD symptoms typically start in the tween years, though diagnosis may not occur until the teen or young adult years, it's important to study children with sub-clinical symptoms, she notes.

Though the study involves in-person interactions for the brain scans, the CBT exposure therapy is done through video chat. In fact, Fitzgerald says, this can make it easier for children and teens to confront the item or situation that triggers their OCD-like impulses, because these are often found in the home environment.

"We need families and patients to engage with researchers in studies like these," says Fitzgerald. "Only through research can we understand what works best for different groups of patients. And perhaps by doing so we can expand the availability of the most evidence-based OCD therapies – including by engaging psychologists and clinical social workers in leading treatment programs, in addition to psychiatrists at specialized centers."

Get more information about current and future clinical trials at U-M and NIH for OCD and related conditions.

In addition to Taylor, Norman and Fitzgerald, the study's authors are Kristin A. Mannella, B.A., Huan Yang, M.D., Ph.D., Mike Angstadt, M.S., James L. Abelson, M.D., Ph.D., and Joseph A. Himle, Ph.D. The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH102242). The study's ClinicalTrials.gov identifier is NCT02437773.

Paper cited: "Treatment-Specific Associations Between Brain Activation and Symptom Reduction in OCD Following CBT: A Randomized fMRI Trial," American Journal of Psychiatry. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19080886

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!