Doctors often care for people with disabilities, yet few physicians have one. U-M’s medical school recently altered its technical standards to better promote a longtime mission of inclusivity.

7:00 AM

Author |

An injury from a water polo practice during his freshman year of high school left Chris Connolly a quadriplegic at age 15.

The Chicago native spent years regaining limited mobility in his arms and legs, skills he continued to sharpen while earning bachelor's and master's degrees at Stanford University.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"I now have pretty good handwriting — for a guy, I guess," says Connolly, now 25. "And I've been doing a little bit of walking. It isn't pretty. I'm not going to be a runway model anytime soon, but that's OK."

But when researching medical schools, Connolly discovered many programs had technical standards that require students to perform physical tasks such as CPR and lifting a patient. So despite his mental aptitude, he couldn't enroll.

Technical standards vary by institution. Their purpose — to ensure a uniform set of attributes among enrollees — is universal. Such benchmarks, beyond motor skills, typically range from scientific acumen and problem-solving skills to the emotional capacity needed to interact with patients and hospital staff.

In many places, these standards have not changed since 1979, when the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) issued recommendations for a universal skill set among applicants to ensure success in any specialty.

This has led to more recent debate over whether technical standards, even indirectly, exclude qualified candidates who have a disability.

At the University of Michigan Medical School, where Connolly started his first year in August, his limitations aren't a deterrent. The school revised its technical standards in 2016 to include students with compromised physical function, as long as alternative or supplemental means can help them learn the hands-on coursework.

In addition to physical and chronic health disabilities, the school can accommodate students with learning disabilities (such as dyslexia), mental health conditions (anxiety) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by offering extra time on exams or a testing environment with limited distractions.

The move, one educator says, reflects the true aim of medicine and medical education.

"As physicians, we don't turn anyone away; our responsibility is to address every individual," says Steven Gay, M.D., M.S., assistant dean for admissions at the U-M Medical School. "By the same token, there is no substitute for learning with people who are different from you.

"Everyone needs to have a seat at the table."

There is no substitute for learning with people who are different from you.Steven Gay, M.D., M.S.

Changing attitudes

Although the shift seems like a no-brainer, it isn't widespread. Based on current language, technical standards at some other institutions could be interpreted as discriminatory.

SEE ALSO: What the Michigan Med School Admissions Team Looks for On Applications

"Many of them might be illegal, frankly," says Rajesh S. Mangrulkar, M.D., associate dean for medical student education at the U-M Medical School. "Legal experts say some of these wouldn't pass muster under the Americans with Disabilities Act."

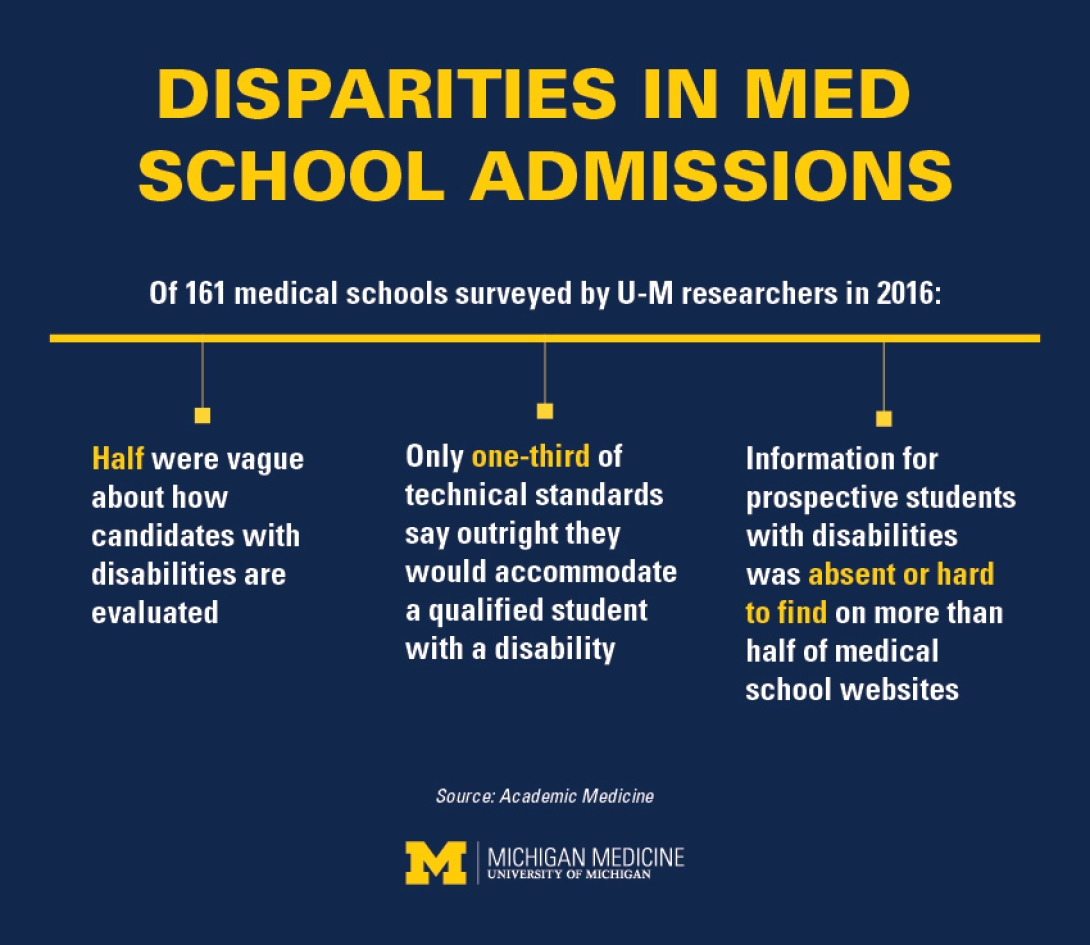

Nor are they always transparent: A 2016 paper co-authored by Michigan Medicine physicians Michael McKee, M.D., MPH, and Philip Zazove, M.D. — both of whom are deaf and are advocates for people with disabilities — argued that technical standards too often are "vague and not clearly presented in the school admissions materials or on schools' websites."

The paper in AMA Journal of Ethics noted that no legal case, to the best of the authors' knowledge, has centered on patient harm resulting from a disabled doctor requiring special assistance.

The writers also cited a clear disparity: While 19 percent of noninstitutionalized people in the United States have a disability, less than 1 percent of medical students do.

Another study co-authored by Zazove found only one-third of 161 surveyed U.S. medical schools have technical standards that directly address students with disabilities.

It might explain why Michigan's recent change drew attention from the AAMC, which administers the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). The association contacted Mangrulkar to learn how the standards were implemented — and whether the nonprofit body should advocate that other schools follow suit.

The move at Michigan required careful thought and planning. Representatives from the school's disability services and legal teams, among other departments, provided feedback via committee. Students and staff with disabilities weighed in, too.

The resulting updates, congruent with the ADA and disability law, state that "reasonable" accommodations can be made for differently abled students, who must be able to pursue their medical educations using supplemental tools in a manner similar to their peers.

That might mean using an acoustically augmented stethoscope for pupils with hearing loss. Or a proxy assistant to maneuver a patient's limbs when a person with limited arm strength is unable.

The new language, Mangrulkar notes, isn't meant to be a recruiting tool but instead is meant to reinforce transparency that Michigan welcomes any applicant.

Nonetheless, "we are definitely leaning in on this," he says. "It's something we care about deeply."

Making resources available

Ethical considerations aside, inclusivity offers medical schools more incentive than a reputational boost: It also is key to maintaining institutional grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, among other sources.

"It is important that outreach and efforts are being made to recruit and retain individuals with disabilities," says Matt Holliday, Ph.D., M.Ed., a learning specialist at Michigan's medical school who helps match students with the proper assistance. He also promotes available services such as tutoring and mental health counseling to others.

SEE ALSO: To Achieve Diversity Among Doctors, Start in Pre-Med Years

Occasionally, students are diagnosed with a disability after matriculation. "We're here for support at any point," says Holliday.

Any enrollee seeking assistance must register with the university's Services for Students with Disabilities office, which can provide evaluation and help determine a course of action. Each request is reviewed case by case, Holliday says.

The needs are varied: Connolly, for one, relies on talk-and-type software when he isn't able to write (he's honing that skill with a special pen and sometimes an Apple Pencil). At 6 feet 3 inches tall, Connolly — who uses a wheelchair — also uses a higher table in the classroom.

"It's a very accessible environment," he says.

Even minor adaptation in unexpected circumstances can make a difference.

A few weeks ago, Connolly experienced pain from the leg braces that he wears with dress shoes shortly before starting patient-facing coursework that requires students to dress up. He was allowed to wear sneakers instead.

Different abilities, shared goals

Connolly knows that he doesn't have the function to be a surgeon or an emergency department physician. He's interested in a career in pediatric genetics, a role that requires a strong brain above all else.

"Medicine is a very complex field with tasks that don't require a ton of physical, hands-on work," he says. "And a medical degree can be used in different ways by working in policy or business or law."

Mangrulkar also values that mindset. But he knows that institutions, including his own, historically have felt that they trained students to be able to enter any branch of medicine.

SEE ALSO: Virtual Humans Help Aspiring Doctors Learn Empathy

Removing physical attributes from the equation changes that one-size-fits-all trajectory — a notion that Michigan officials weighed when changing their technical standards.

"At the end of the day, we had to ask ourselves a fundamental question: Should every student from this medical school be able to go into any residency?" Mangrulkar says. "We've known for a while that the answer is no."

One belief leading to that conclusion is that a diverse student body helps budding doctors gain a greater empathy for the populations they will one day treat.

Says Gay, the medical school assistant admissions dean: "You can read about taking care of a patient who is disabled, but watching a doctor who is disabled working with them and understanding the challenges they're going through will give you infinitely more information about their needs than you can get from reading a textbook."

It also attracts top students who could otherwise go elsewhere.

"I knew some schools wouldn't be interested in me; that's because of their technical standards, to be honest," says Connolly, who disclosed his limitations during the application process.

After accepting him, Gay phoned the prospective student. That conversation, Connolly says, solidified his decision to enroll at Michigan, leaving no doubt that his disability wouldn't be an issue.

"Dr. Gay said: 'Once you're in, you're family — and we take care of family.'"

Photos by Leisa Thompson

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!