Suppressive Treg cells become even more suppressive when they die, a new study finds.

12:00 PM

Author |

Researchers have uncovered a surprising process within a key immune cell that may help explain the limitations of immunotherapy as a cancer treatment.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

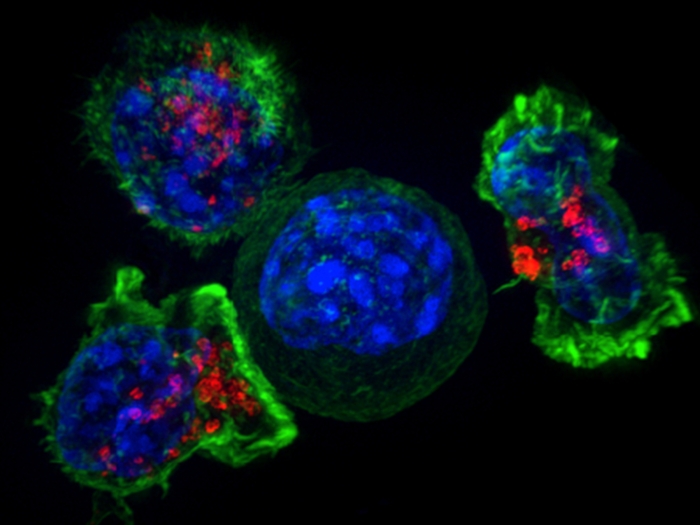

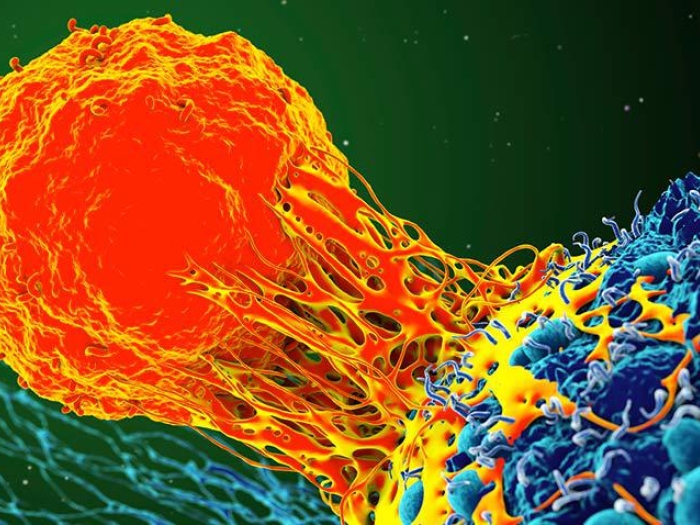

Regulatory T cells, or Treg cells, work within the immune system to suppress immune function. It's a normal process: T cells fight an infection, and when the threat is over, Treg cells send the signal to stand down.

Cancer immunotherapy treatments work by supercharging the immune system to fight cancer. So when Tregs come in and suppress the immune response, it shuts down the cancer-fighting effect.

But eliminating the Tregs doesn't help. Researchers have tried, but a clinical trial testing that idea showed no benefit to patients.

Now, more than a decade after discovering the immunosuppressive role of Tregs in human cancer, a new study in Nature Immunology finds that eliminating the Treg cells doesn't eliminate their suppressive qualities.

When the Tregs die, instead of being negated, they become even more suppressive. All the cells are dead, but the machine is still running.

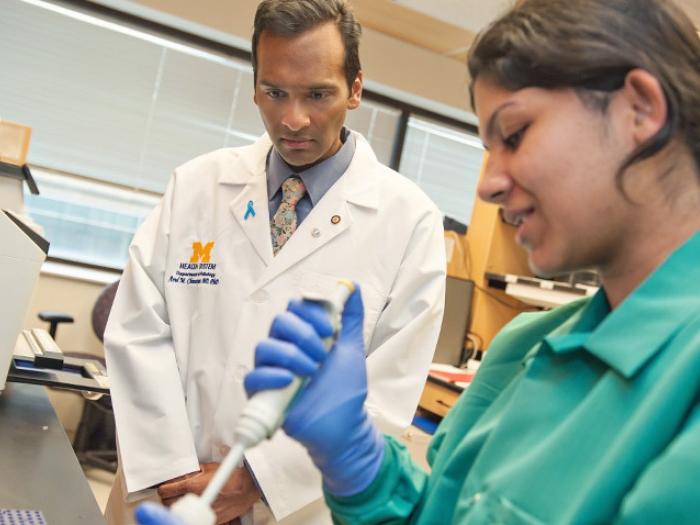

"It's a double-edged sword: If they do not die, they are suppressive. But if they die, they are even more suppressive," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., the Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of Surgery, Immunology and Biology at the University of Michigan.

"Nobody expected this — it was a total surprise. But it likely explains why you don't see benefit when you induce Treg apoptosis," he says.

It's a double-edged sword: If they do not die, they are suppressive. But if they die, they are even more suppressive.Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D.

Next steps for the work

Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment, but limitations and questions remain. One of the biggest questions is why such a small number of patients are responsive.

SEE ALSO: Gaming Cells to Turn Off the Metastases Switch in Breast Cancer

In 2004, Zou's lab discovered that Treg cells were acting against cancer immunity. The researchers linked higher numbers of these cells to shorter survival in patients. That work led to the failed clinical trial designed to eliminate the Treg cells.

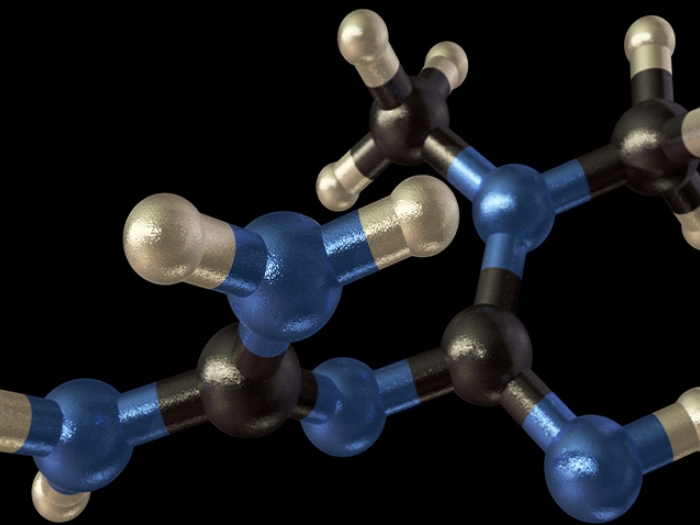

It turns out, this new study finds, that when Treg cells die, they release a lot of small metabolites called ATP. Usually ATP helps supply the body with energy. But dying Tregs quickly convert ATP to adenosine. The adenosine then targets T cells, binding to a receptor on the T cell surface. This affects the function of the T cells, making them unhealthy.

Tregs travel to the tumor from throughout the body, which explains Zou's earlier finding that there are many Tregs in a tumor. But while the Tregs proliferate, they are dying fast at the same time. So there are many Tregs but also many dying Tregs.

Researchers will next look for ways to limit this function by creating a roadblock to prevent the cells from migrating to the tumor microenvironment. They will also investigate options to block or control the suppressive activity.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!