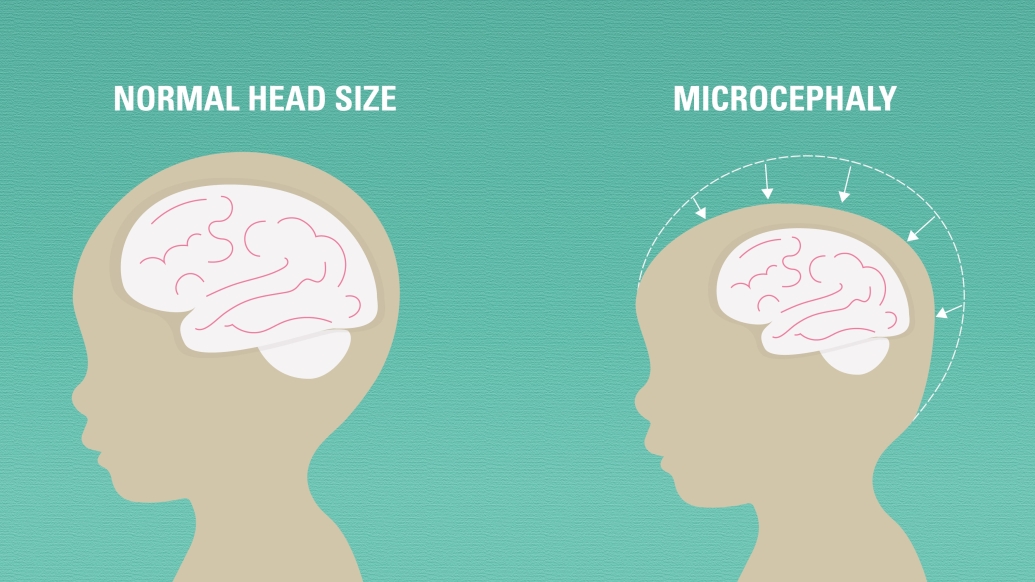

The link between the birth defect microcephaly and the Zika virus has raised alarm. Now, a new examination of non-Zika cases could help scientists understand why microcephaly occurs in any patient.

1:00 PM

Author |

Long before the Zika virus made it a household word, the birth defect microcephaly puzzled scientists and doctors.

SEE ALSO: What You Need to Know About Zika This Summer

But new discoveries from an international team of scientists may help explain what happens in the developing brains of babies in the womb, causing them to be born with small brains and heads.

The findings may also help scientists studying why Zika may cause the same condition in some babies born to mothers who catch the virus from a mosquito bite.

In two new papers in the American Journal of Human Genetics, researchers report new findings about a key protein involved in generating the many new cells required to build a normal-size brain.

Stephanie Bielas, Ph.D., a University of Michigan Medical School assistant professor of human genetics who helped lead the new research, says the findings provide insight into normal brain development.

"There's so much we don't understand about human brain development that we're just starting to uncover," she says. "This shows the devastating impact of interrupting cell biology critical for this process."

We need to know how microcephaly genes are contributing to such a profound human disorder. It's a puzzle. So let's figure it out.Stephanie Bielas, Ph.D.

Interrupted cell division and brain development

Both papers focus on citron kinase, a protein important during mitosis, in which one cell divides into two. Cell division is the foundation of normal growth and development.

CIT, as the protein is called, helps in the final stages of cell division that separates the two "daughter" cells, called cytokinesis. In this process, the two new cells, each with their own copy of the DNA from the original parent cell, sever the connections between them.

Years ago, animal research showed that problems with the gene that drives the making of the animal form of citron kinase could lead to microcephaly. Until now, that link had not been proved in humans. The researchers now say that CIT is critical to building a normally sized human brain.

For this discovery, the researchers turned to families from Egypt, France and Turkey who had one or more microcephalic babies. Some died soon after birth; others developed intellectual disabilities resulting from a too-small brain.

These babies' genes and brain tissue showed the importance of CIT and the problems that arise when the gene mutates. Where normal brain cells have only one nucleus — the pouch containing the DNA and other important structures — many cells in microcephalic brain tissue had multiple nuclei. This suggested something happened to prevent new cells from dividing properly.

Stem cells helped the researchers take the study further. Using skin cells from the surviving children, they transformed the cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). This essentially turns back the clock on the cells, making them able to develop into nearly any type of cell.

The researchers then grew the iPSCs under special conditions that coaxed them to develop into neural progenitor cells — those that, in a developing embryo, grow and divide rapidly to become the future child's brain.

"There's a lot of evidence now that in microcephaly, there aren't sufficient numbers of neural progenitor cells to build the normal-size brain," says Bielas. "Since the cells that form the structures of the brain and develop into the different types of cells are born from this pool of actively dividing cells, this aspect of human brain development is a key issue to study."

Bielas says studying rare spontaneous cases of microcephaly — such as those in the families that took part in the study — offers a chance to identify genes important for brain development and to understand the impact of deleterious, small genetic mutations.

"Often in genetics, we identify seemingly obscure genes as the genetic basis of disorders; we don't know what they do or where and when they're active," she notes.

"But in the case of citron kinase, we knew what a mutation in the gene did in animal models. These newly published findings confirm that CIT mutations are not only linked to severe microcephaly in humans, but are also associated with a smooth, unfolded brain surface — a condition known as lissencephaly — that isn't usually seen in brain disorders linked primarily to defects in neural progenitor cell mitosis."

Bielas and her colleagues are now creating brain "organoids," or balls of brain tissue grown from iPSCs or human embryonic stem cells with edited genes, to study this issue further. Some Zika researchers are also using this promising model system to study the virus's effect on human neural progenitor cells.

Bielas is seeking more families whose babies have been born with non-Zika microcephaly to contribute skin and DNA samples, which may yield more clues about the condition's origins.

"We need to know how microcephaly genes are contributing to such a profound human disorder," says Bielas. "It's a puzzle. So let's figure it out."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!